The United Left Alliance and the Rise of Working-Class Politics in Ireland

On Friday February 25th, the Irish people voted in what Fine Gael‘s leader Enda Kenny proclaimed a ‘democratic revolution.’ The results of this election are transformative with the unparalleled decimation of the once dominate Fianna Fail. This left Fine Gael and Labour riding a wave of voter discontent into power. It will likely only be a matter of time, however, before Irish voters who thought they were voting for change realize that they simply traded one neoliberal government for another.

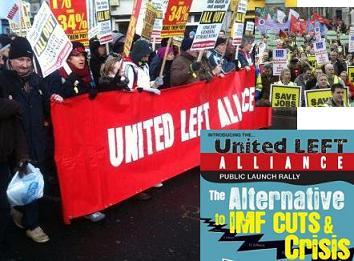

Aside from the large voter swing to Fine Gael and Labour, record levels of support were given to the proclaimed ‘leftist’ Sinn Fein and Independents of all political stripes. As well, a new political force entered the Dail (the Irish lower house of parliament) for the first time, and already starting to build their movement of opposition to the expected political direction of the new government. Formed under the banner of the United Left Alliance (ULA) in November 2010, the ULA’s five elected candidates gathered under a new political model that may pose the first meaningful challenge to Ireland’s ruling classes since liberation from British rule.

Aside from the large voter swing to Fine Gael and Labour, record levels of support were given to the proclaimed ‘leftist’ Sinn Fein and Independents of all political stripes. As well, a new political force entered the Dail (the Irish lower house of parliament) for the first time, and already starting to build their movement of opposition to the expected political direction of the new government. Formed under the banner of the United Left Alliance (ULA) in November 2010, the ULA’s five elected candidates gathered under a new political model that may pose the first meaningful challenge to Ireland’s ruling classes since liberation from British rule.

A New Alliance

The ULA is, in fact, an alliance of political activists from the Socialist Party (SP), the Socialist Workers’ Party (SWP), activists who left the Labour Party along with community activist groups such as People Before Profit (PBP) and the Workers and Unemployed Action Group (WUAG) in Tipperary and others; campaigned on a political Programme and structure unlike any other.

Some key points of ULA Programme are: working for “democratic and public control over resources so that social need is prioritized over profit”; and being “committed to building a mass left alternative to unite working people, whether public or private sector, Irish or migrant, with the unemployed, welfare recipients, pensioners and students in the struggle to change society.”

Due to being an alliance of political and community activists, the emphasis in this election was maintaining a horizontal, democratic structure that allowed candidates to campaign under the ULA banner as long as they signed a pledge to adhere to the principles of the ULA. This strategy of working together on issues of agreement served to break decades old divisions on the Irish left, and suggest that the ULA has much further potential as a new left movement.

As discussed by Brendan Young in “Building the ULA: Reflections on the Past and Proposals for the Future,” the ULA’s open structure also has some potential tensions. Now that a measure of electoral success has been achieved, serious discussions will need to occur about whether this will continue being an alliance or a formal party that will lead their new movement. With equal numbers of candidates being elected from the SP and PBP, this can either serve as a point of division or a means to ensure the right balance is achieved between these visions.

These events would have been unimaginable a decade ago when Ireland was the model of a successful neoliberal state: a political system dominated by a political duopoly between the Fianna Fail and Fine Gael parties that controlled all Irish governments since independence; a deeply entrenched capitalist class in all Irish institutions; and a dominant culture under the influence of a reactionary church ruling over a fragmented opposition.

Political Duopoly and the Celtic Tiger

How such an entrenched ruling class came to power and the difficulty of challenging their rule is firmly grounded in Ireland’s past. One hundred years ago Ireland had a powerful working-class movement that waged general strikes, formed socialist parties (including the Labour Party) and took up arms in the Easter Rising in 1916. This movement, however, relied heavily on its leadership, and was further compromised after the executions and emigration of many of its leading cadres.

In 1918, in a decision that became infamously known as ‘Labour must wait,’ the now weakened Labour Party and trade union movement decided to support Eamon de Valera’s nationalist campaign in that year’s general election instead of fielding their own cadidates. This decision subordinated a once vibrant working-class movement to a hostile economic class and conditioned the people to prioritize nationalist issues over their own.

The subsequent decision to not contest the election in 1921 ensured the working-class movement (which had support on both sides of the sectarian divide) was essentially left out of the negotiations that divided the nation through the Anglo-Irish Treaty. The Labour Party finally contested the elections in 1922. But by then it was too late as the nation was hopelessly divided into those in favour or opposed to the Treaty resulting in the Irish Civil War.

These nationalist divisions ensured that whoever would lead the country, Ireland’s capitalist class would remain firmly in control. This has been the recurring pattern of Irish politics, with a docile Labour Party occasionally playing the role of a junior partner to the dominate Fianna Fail (anti-treaty) and Fine Gael (pro-treaty) parties. Decades of this duopoly resulted in Ireland becoming an inward looking conservative state.

Ireland’s entry into the European Economic Community in 1973 allowed new opportunities to slowly build toward an alternate model, eventually culminating in the neoliberal ‘Celtic Tiger’ of 1995 to 2008. This ‘Tiger’ was created by using European subsidies for education and infrastructure whilst enticing foreign multi-national corporations with low corporate taxes, weak labour standards, de-regulation and corporate subsidies to establish their European operations there.

The multinational investment and subsequent Irish export surge also helped create the conditions for a property boom fuelled by rampant speculation through a de-regulated banking sector. This boom created some 200,000 more houses than the housing market, at massively speculative prices, could bear. When these ‘ghost estates’ went bust, the government spent billions in bailing out Irish banks and their speculative investors, many of whom were European banks who under girded the massive leverage of the Irish banks and the astonishing levels of financialization relative to growth of the productive economy. The utter collapse of the Celtic Tiger, and the subsequent fiscal crisis of the Irish state caused by the decision to cover Irish bank losses, was, not surprisingly, the dominate theme of the 2011 election. It has exposed the corruption and cronyism that has been at the heart of the Irish state and the governing coalition led by Fianna Fail.

Sources of the ULA

The roots of the ULA predate this economic collapse as there are two other equally profound developments that have shaken the ruling classes’ dominance over Irish society. The first is the sex abuse scandals that are rocking the Roman Catholic Church. These scandals are leading to a potentially irreversible challenge to the church’s historical influence over society. This cultural transformation is profound and is finally freeing Irish working-class movements from the reactionary opposition of the Church.

The other is that the Fianna Fail/Fine Gael duopoly has shown it can be defeated. In 2008, Irish voters rejected the Lisbon Treaty that was endorsed by both parties. This sent shock waves throughout the establishment in Ireland and Europe. Left wing activists were instrumental in this campaign and freed from the usual political debates, the people responded to the issues instead of their traditional party loyalties. By uniting their fragmented movements together, it demonstrated that victories could be achieved.

At the local level, important and empowering victories were also achieved. Although these often dealt with local matters, by fighting on specific issues and winning a range of local elected positions, they provided a platform for new political ideas. These victories created new alliances and activists upon which to build a political base to articulate working-class perspectives that have changed the political dialogue.

Reflecting Ireland’s historical challenges, the ULA has purposely set an agenda that focuses on patiently building a sustainable political movement. They achieved their goals for this election: electing five of TD’s (Teachta Dálatha – member of the Irish lower house); positioning themselves for the inevitable disillusionment of the new government by not supporting any of the neoliberal parties; articulating clear alternatives; and establishing a solid base upon which to build.

Transforming Economic Policies to Action

As evidenced by the results of this election and the way they scared the Irish voters in 2009 to accept the Lisbon Treaty in a second referendum, Ireland‘s ruling class will not go quietly. Cleary breaking this political duopoly, with its social democratic third partner in Labour, will take time.

This is already starting to happen as evidenced by the record number of voters who rejected all three of these parties or even voted for the first time for another of the dominant parties. As with the referendum victory in 2008, a political transformation has occurred as the Irish people are ending their traditional party loyalties and focusing on the issues raised by the economic crisis and the undemocratic features of the Irish state.

Although there has been a cultural shift and the beginnings of a political transformation, there has not been an economic one. Anti-capitalist economics has to move beyond policies toward democratic and public control of the means of production in a way that cannot simply be undone by another bourgeois government.

There are also a number of economic alternatives that can be advanced that build working-class capacities and act as structural reforms against capitalist social relations. These are initiatives such as community ownership, worker co-operatives, collective enterprises and others that can be built now, as opposed to simply waiting for a moment of rupture or political breakthrough. With neoliberal capitalism exposed as sponsoring an elaborate financial Ponzi scheme in Ireland, there is a willingness to explore new ideas that move beyond proposals to action.

During the campaign, ULA candidates raised concerns about the effects rising interest rates and falling property values could have on the working-class. Thousands could lose their homes due to foreclosure and it’s highly likely the new government will not adequately address this problem. At the same time many ‘ghost estates’ sit empty. Since these estates have become public property due to the bank bailouts, they should become low cost public housing. If the government also refuses this solution, then it might be worth considering putting Ireland’s laws of “Adverse Possession” (use it or lose it) to productive use through direct action to convert them to community co-operative housing for the victims of the economic crisis. In the right economic conditions and with a measure of political boldness, a lot of support can be built around this action as evidenced by the agricultural and worker recovered enterprise movements in countries such as Brazil and Argentina.

As with the initial smaller political victories, these economic alternatives can show the tangible benefits of creating a new economic order that truly does place people before profits. If this is successful, they would provide a powerful base of support to affect the larger changes needed if and when political victories occur.

Attempts should also be made to involve trade union activists in these alternative projects so they can gain experience in transforming their movement into one that goes beyond trying to get a bigger piece of the capitalist economic pie to one that empowers the entire working-class.

Two days before being elected as a TD, ULA (SP) candidate Joe Higgins stated: “With a good result the United Left Alliance will be in position to launch a new political movement of the left, a new political party of the left that is an alternative to the entire establishment.”

These comments were made in Dublin under the statue of the trade unionist and political activist, James Larkin. At the pedestal of his statue are the words that, one hundred years ago, inspired Ireland’s working-class to change their world – “The great only appear great because we are on our knees. Let us Rise!” Now that the ULA has achieved their breakthrough, it’s great to see these words taking on renewed meaning. Let the democratic revolution begin! •

Resources:

- Harry Browne, “Electoral revolt against austerity, left makes big gains.”

- William Wall, “The Irish Election 2011 – A success for the Left.”

- Brendan Young, “Building the ULA: Reflections on the Past and Proposals for the Future.”

- “United Left Alliance’s electoral challenge strengthens”