Race and Policing: Inquiry into Police Killing of Frank Paul Shows Power of Protest

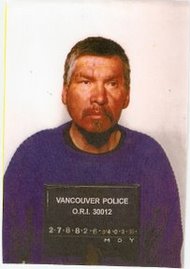

On December 5, 1998 a Vancouver police officer dragged Frank Paul, a 47-year-old Mik’maq man, soaking wet and unconscious, from the downtown holding cells and dumped him in an alley across town. He was drunk and could not stand or speak clearly. His body was found at 2:30 am in the same alley by a passerby.

According to the pathologist’s report, Paul had died of hypothermia accelerated by acute alcohol poisoning. He was likely already dying of hypothermia when Sergeant Russel Sanderson ordered the rookie wagon driver Constable David Instant to dump Frank Paul into the night.[1]

According to the pathologist’s report, Paul had died of hypothermia accelerated by acute alcohol poisoning. He was likely already dying of hypothermia when Sergeant Russel Sanderson ordered the rookie wagon driver Constable David Instant to dump Frank Paul into the night.[1]

How the police investigate the police

If Frank Paul’s death is tragic, the investigation process that followed is frightening and infuriating.

The death of Frank Paul was investigated by Detective Robert Douglas Staunton – one single officer. Staunton later said that he pursued his investigation “in a way I thought would be neutral.” At the recent inquiry Staunton testified that “neutrality” meant he did not seek to find fault. In fact, he worked to obscure evidence of the criminal actions of the police. In contravention of police regulations, Staunton did not perform any of the routines normal for a homicide investigation.

This break with routine is the norm for police investigation of police crimes. Between 1992 and 2007, 52 people died at the hands of members of the Vancouver Police Department (VPD). Not a single one of these deaths resulted in charges being laid against a single officer.[2]

Why this “neutral” stance in cop killings? Staunton explained that unless, before the investigation started, it was already known that the suspected police-criminals “were absolutely guilty of a criminal offense, it basically served no purpose,” because if investigators took steps towards prosecution “we would receive no information.”[3] An astonishing admission! What is more, “that is a practice that the Major Crime investigators followed” in all 52 or so cases of deaths at the hands of the police in the previous 15 years, he said. “We didn’t make judgments.”

Former Vancouver coroner and former mayor Larry Campbell confirmed Staunton’s description of police practice, telling the inquiry that as coroner he would always take the word of the investigating officer over that of crown prosecution on the viability of charges.[4] Don Morrison, police complaints commissioner at the time of the Frank Paul killing relied on the same “neutrality” when he opposed calls for a public inquiry in 2001 saying, “What do you want me to do, wreck a young officer’s career?”[5]

Morrison’s stonewalling came at the prompting of BC’s Liberal government. Solicitor-General Rich Coleman wrote Morrison that year explaining that he would not open a coroners inquest into Frank Paul’s death where “culpability, liability and issues of racial discrimination are likely to become the central features…. [A] responsible coroner would not permit the pursuit of those matters. Public acrimony would almost certainly follow.”

Staunton’s “neutral” investigation in fact paralyzed any process of accountability for the death of Frank Paul. No disciplinary actions resulted beyond the light slap on the wrist delivered earlier by the VPD itself following its internal investigation: a one-day suspension for Instant, and two days for Sanderson.

Complaints process exposed

In the final days of the public inquiry, Mike Tammen of the BC Civil Liberties Association accused the Vancouver Police Department of cover-up. In fact, the cover-up was not solely the work of the police. From the original police “investigation” to the Office of the Police Complaints Commission, to the Coroner, to the BC Liberal government, all authoritative bodies barred the door against any investigation or inquiry into the killing of Frank Paul. A conspiracy of silence around Frank Paul’s death continued, virtually without exception, until early 2007. The NDP fell into step, and did not speak a word about Frank Paul until halfway through the inquiry.

The Frank Paul cover-up is only too typical of standard police procedure. In a document called “Towards More Effective Police Oversight” the Pivot Legal Society explains how complaints against police in BC are processed.[6] The complaints process is compromised from start to finish, the Pivot document shows, by the

watchful eye of the police, backed up by the government and ruling elite that the police protect.

The report cites John Westwood of the BC Civil Liberties Association, “I have never met an internal investigator who is biased in favour of a civilian complainant…. Nor have I assisted in a complaint where the police witnesses support the complainant’s account of events in opposition to the accused officer’s account.”

The Pivot Society calls this the “blue code between officers which undermines the public interest in police accountability.”[7]

Role of police in society

The “blue code” serves the underlying role of police in society as protectors of the status quo of capitalist property relations. The heavy arm of policing falls on capitalism’s victims – especially the poor, the sick, and racialized people.

It is quite true that neither Constable Instant nor his colleagues create the conditions that killed Frank Paul. The set-up was carried out by the provincial and federal governments, in collaboration with the Downtown Eastside real estate barons who sit on block after block of empty buildings as speculative investments, and with the big capitalists who juggle market relations to maintain a reserve army of labour in the person of people like Frank Paul.

The neoliberal reforms carried out by the BC Liberal government and its counterparts in other provinces have a clear agenda – to deepen the suffering of poor, oppressed, and working people. Police are called in to put down dissent. Hundreds of years of colonial genocide and repression have hammered people like Frank Paul in order to steal and plunder the land of the Mik’maq and other Indigenous nations.

David Dennis, the Vice-President of United Native Nations (UNN), an organization that represents off-reserve Indigenous peoples, sees police institutions as being responsible for the day-to-day oppression and racism that many native youth experience. “There’s a direct relationship between the way the police are treating these young people and the way that these young people end up getting dead.”[8]

How the inquiry was won

Despite all of these systemic barriers, a demand for a public inquiry came out of the Indigenous community in Vancouver, and an inquiry was won. A major factor in making Frank Paul’s death an issue big enough to force an inquiry was the work of Kat Norris and the Indigenous Action Movement (IAM). In an interview conducted in the last days of the public inquiry, Kat Norris explained that she was motivated to organize for Frank Paul because “what happened to him should not happen to anyone. The gall of racism just hit me. I just couldn’t let it go by without doing something.”[9]

It’s instructive to compare this case with the killing of would-be Polish immigrant Robert Dziekanski by taser-wielding cops at the Vancouver airport on October 14, 2007. That case too would no doubt have been covered up if the unprovoked attack hadn’t been captured on video. But once it was public, the death of a European immigrant generated far more response – including from the corporate media – than the death of a homeless Mik’maq.

The United Native Nations was the first organization to lay a public complaint about the death of Frank Paul in 2002,[10] and it remained involved throughout the public inquiry. UNN took an interest in Frank Paul’s case because, David Dennis explained, it confirmed “our fears about the police’s role, the cover-up that occurred, and the kind of the complicity of the provincial government to keep this death at the hands of the police suppressed for so long.”[11]

Limitations of the Frank Paul inquiry

It wasn’t until February 2007 that the government allowed the public inquiry to go ahead, while barring it from finding fault or laying charges.

The very fact that the death of Frank Paul, which had been covered up, lied about, and silenced for nearly ten years, made it to a public inquiry is a testament to the strength and potential power of social movements. However, the Frank Paul inquiry can only be considered a partial victory for the movement that fought and organized for it.

Kat Norris points out that although Const. Instant “is being used as a scapegoat to take the blame (…) he was following someone’s orders.” And David Dennis explains, “There are limitations to the inquiry, and we’ve been really vocal about how it’s not designed to assign fault. But it can assign responsibility to people and with that we can take it further.”

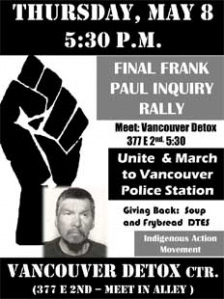

The final stage of the Frank Paul inquiry will take place April 28 to May 16 with government and police policy hearings. While the inquiry commission cannot place binding recommendations on the government or police, it has and will present a platform where demands can be put forward. UNN presented their demands at the inquiry hearing on May 1, and IAM will be making their demands heard in the streets with a march from the Vancouver Detox to Main and Hastings on May 8.[12]

For both UNN and IAM, the inquiry has opened a window to bring pressure against higher places in the police administration and government. David Dennis said, “We need someone like Police Chief Graham or Solicitor General Coleman to go down. These are the ones who knew about [the killing of Frank Paul] and didn’t do anything about it.”[13]

Development of movement demands

Kat Norris wants “to bring the police to justice. Someone has to answer for what happened to him. Someone needs to be held accountable. I want for this to never happen to one of my people again.” For her, the inquiry itself has been “a sign of how much power the police and the justice system has over its own … they take care of their own. The police and the higher-ups are great friends. I’ve always said that just by instinct. But you can see it. It all goes back to land ownership and the corporations.”

David Dennis and the UNN are working out a more ambitious program of reform, beginning with “tangible things that can be changed” like challenging the provincial contract for the RCMP that comes up for renewal in 2012.

The UNN calls for civilian investigations; but Dennis recognizes the potential problem of corruption in such a civilian investigation body. Volunteers for a similar group in Ontario are mostly former cops. The other danger is that people who join also quickly adopt the mentality of the “Blue Shield.” To protect against these trends, UNN is demanding that membership in such a body be based on recommendations from Indigenous community groups and leadership. “People who are there are our eyes,” he says. “It’s kind of one step up.” In this way, such civilian investigation units could be linked with the grassroots movements and mass organizations that will fight to keep them in line.

Reform and the need to survive

Both Dennis and Norris focus on Indigenous peoples’ struggle for survival against police repression. Police racism, harassment, brutality, and even murder are a grim reality for Indigenous peoples, particularly those who live off-reserve in urban centres.

In an article published by the United Nations Chronicle in 2007, Melissa Gorelick quantifies the hostile relationship between the Canadian “justice” system and Indigenous peoples. “According to the Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics, aboriginals make up about 19 percent of federal

prisoners, while their number among the general population is only about 3 percent [see note [14]]. Between 1997 and 2000, they were ten times more likely to be accused of homicide than non-aboriginal people. The rate of natives in Canadian prisons climbed 22 percent between

1996 and 2004, while the general prison population dropped 12 percent.”[15]

Kat Norris points out that Frank Paul “represents the discrimination, racism, murder, sexual abuse, residential schools, colonization that our people have suffered. He represents our people.” And she draws a connection between police harassment and colonization. “We’re suffering simply because the imperial powers desired our land.”

In the face of this brutal oppression, oppressed peoples respond with strategies for survival. Their day-to-day struggle against police violence contributes to the process of getting rid of police and prison institutions along with the entire capitalist structure they serve.

The front lines of struggle

The Indigenous community has taken on the struggle against police repression more consistently and effectively than any other community in Canada. The work of United Native Nations, the Indigenous Action Movement, the Downtown Eastside Womens’ Centre Elders Council, and Knowledgeable Aboriginal Youth Association in Vancouver practice important examples. They must not be left to struggle alone. They need broad and effective support.

Racialized people all across Canada are familiar with the club and gun of the police departments – whether you are Latino or South Asian in Vancouver, Black in Toronto, or Arab in Montreal. The same is true of the multi-racial communities of the hand-to-mouth poor, homeless, drug users, and mental health consumers in neighbourhoods like the Downtown Eastside of Vancouver. We should work to forge unified action groups between these diverse communities and cultures and their supporters.

White workers also have a strong stake in supporting these struggles. First, racist treatment must be opposed because it divides working people and violates the human dignity of us all. Second, police are also the enemies of the labour and activist movements as they struggle for progressive change. Unionists who have found their strikes and actions attacked by police defending the bosses’ interests understand this well, as do activists who have been beaten up and arrested by police because of their actions for social justice.

The movement for a public inquiry into the police killing of Frank Paul holds an important lesson. Without a grassroots struggle in the streets, the demands of the movement – survival-based or otherwise – would not have carried weight. In fact, the street movement is where the demands are rooted, and where survival-based demands for reform can move forward.

The movement that Kat Norris has helped initiate has a potential to advance both the survival struggle and the broader movement against police violence, provided it is backed by the mounting pressure that only a street movement can advance. The breadth and strength of the grassroots movement against police brutality will decide how powerful and far reaching these demands can become. •

Footnotes

1.

Frank Paul inquiry, Jan 7 2007, testimony of Sanderson.

2.

Frank Paul inquiry, Feb 14 2008, testimony of Staunton.

3.

Frank Paul inquiry, Feb 14 2008, testimony of Staunton.

4.

Frank Paul inquiry, Jan 25 2008, testimony of Larry Campbell.

6.

“Towards More Effective Police Oversight”, Pivot Legal Society, September 2004

7.

“Six Recommendations for Policing Reform”, Pivot Legal Society, Fall 2005 (Pg. 1)

8.

“Interview with David Dennis”, Ivan Drury, March 26, 2008.

9.

“Interview with Kat Norris”, Ivan Drury, March 27 2008.

10.

“Interview with David Dennis”, Ivan Drury, March 26, 2008.

11.

“Interview with David Dennis”, Ivan Drury, March 26, 2008.

12.

March and Rally organized by

Indigenous Action Movement, May 8th,

5pm at Vancouver Detox (377 E. 2nd Ave, Vancouver)

13.

“Interview with David Dennis”, Ivan Drury, March 26, 2008

14.

Statistics on numbers of Indigenous people in Canada vary greatly depending on the source used. 3% is a common (though dated) government number, based on “Status Indians”

and those voluntarily identified by census. Other sources place Indigenous peoples at between 5% and 10% of the population in Canada. Many Indigenous nations regularly

refuse to participate in the Canada census, and an unknown number of individuals do the same.

15.

“Discrimination of

aboriginals on native lands in Canada: a comprehensive crisis”, UN Chronicle, Sept, 2007.

Resources:

- Indigenous Action – indigenousaction.blogspot.com

- Frank Paul Inquiry – frankpaulinquiry.ca

- United Native Nations – www.unns.bc.ca