When I last visited Bob at his nursing home in Kincardine, a nurse politely pulled me aside to tell me that he no longer talked much but remained quite sociable. The deterioration in his condition was sad to hear, but I remarked that his retention of social skills was no surprise. ‘As a union organizer he had a natural sociability’. She lit up and excitedly whispered to a nearby nurse: ‘That explains it!’. ‘Explains what?’ I asked. ‘Well, the one thing he keeps telling us is: “You know, all of you work really hard but don’t get paid enough; you should get a union”.’

Fighting Concessions

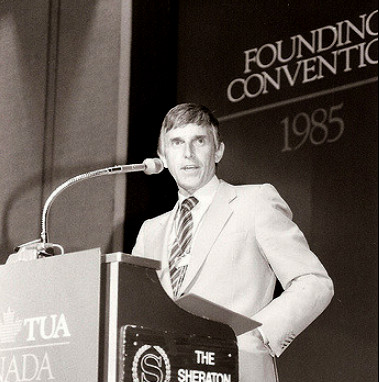

His official legacy, it has long been evident, will rest on his role in not just fighting the auto industry kingpins but the internal battle with his own union. For Bob, breaking away from the union that had been his home and inspiration since he barely got out of his teens was one of the most painful decisions of his life. But that anguished struggle and the creation of the Canadian Auto Workers in 1985 (now UNIFOR) brought out the best in Bob and the Canadian members.

What isn’t always appreciated and speaks to the depth of the union at the time, is the extent to which this ‘split’ was more than an expression of Canadian nationalism (though of course it was that too). The conflict revolved around how the union should respond to the concerted corporate-state attack on social and union gains made in previous decades. This overlapped with questions of union democracy. In the U.S., an opposition had emerged around internal democracy; in Canada the focus was on Canadian workers having to do what was done in no other country – go through a foreign-based parent for approval of key decisions over bargaining demands and the right to strike.

The Canadian autoworkers, unlike the majority of their U.S. counterparts, were adamant not to make the concessions demanded in bargaining. And while Canadian business and the Brian Mulroney government were looking toward further integration with the American empire, the autoworkers were determined to carry on the concession fight even if it led in an opposite direction – in their case breaking away from an American institution.

In bucking the economic and political trajectories of Canadian and U.S. elites, the Canadian workers were in particular taking on GM, Ford and Chrysler, three of the largest corporations in the world. And they were doing so in the most integrated cross-border industry anywhere. With the Canadian industry only one-tenth the size of the overall Canada-U.S. industry, cynical pundits repeated, ad nauseam, that ‘the tail can’t wag the dog’. When the union went on strike against GM in 1984 – the event that most directly precipitated the split with their parent – The Globe and Mail patronizingly editorialized that the Canadian autoworkers “looked staunchly backward.” An editorial in the nationalist-leaning Toronto Star proclaimed “it’s hard to see what they hope to achieve by this strike.” And the Montreal Gazette warned the union it was “remarkably short-sighted.”

Most workers, staff and local leaders were at first very uncertain themselves, not sure that they really had the power or expertise to go it alone. This reflected a semi-colonial mentality that came with past dependence on the UAW and the U.S. more generally. To boot, all the collective agreements in Canada, even those outside the auto majors, were formally signed by the UAW and so were legally invalid if any corporation – or group of workers – decided to challenge them.

The significant achievements of Bob in this period, in addition to his strategic and public handling of all the potential pitfalls, rested on four principles. First, an appreciation that if the Canadians stayed in the UAW, they would become the vehicle for bringing U.S. concessions to Canada. The argument that concessions would provide job security was something that Bob consistently argued against, a view that future developments powerfully confirmed.

Second, concession bargaining didn’t just rob workers of what they deserved but it robbed them of faith in the relevance of their union, something that would inevitably lead to the withering of the union as a social force. Here too Bob’s side of the debate proved to be right.

Third, the key wasn’t just the impact on bargaining but working class self-confidence in the larger sense of Canadians moving out of the shadow of the U.S. union and achieving the right to make their own decisions. This came with taking responsibility for those decisions rather than passively accepting concessions while blaming the Americans for their plight.

Finally, change took preparation and patience. Such radical breaks with the status quo couldn’t occur as a dictate from above; the members needed to be firmly on side. As Bob described it, “we almost completely reorganized our communications network to bring the local union leadership closer to the rank and file. We had to be certain that our membership understood why we were going against the wind.” The union prepared extensive materials, held educational sessions in every local, pushed their stewards to get out on the shop floor and talk to workers, and ordered the staff to “stay close to the members.” Bob spent a great deal of his time going to locals to meet with members and answer their questions and concerns. And the union took the issue to the CLC convention so that it wouldn’t be isolated in the fight against concessions (it was also a way of presenting their tensions with the UAW as not just reflecting that of stubborn Canadian autoworkers but of the Canadian trade union movement in general).

Breaking away could, however, only be broached after workers learned, through battles at Chrysler and GM, that they had the power to go it alone. White’s genius – his true leadership role – lay in his ability to develop the confidence among his members that they could pull the breakaway off and survive. But this itself rested on his own fearlessness in taking on the breakaway (which is not to deny his nervousness about the stakes involved).

Which Side Are You On?

After the split, Bob argued that the funds the Canadians received as part of the settlement should go into organizing and education, the latter to be about union philosophy, history, and political economy. Organizing extended power to other workers and was ‘the backbone of the union’. Education was really a matter of organizing those already unionized as part of strengthening on-going and future struggles. In addition, and speaking to the relationship between breaking the bonds with the U.S. and nationalism, the Canadians became more active internationally after the split, building much closer relations to, for example, workers in South Africa, Brazil, and Nicaragua.

Looking back on Bob’s tenure as a union leader, what sustained him through the turmoil of the times was his clarity over what side he was on. His job was to defend workers. Whatever ‘peace’ was made with employers, he understood that to be temporary and reversible. His original organizing assignment in the 60s – to chase down and unionize runaway plants (i.e. plants moving to escape the union) – left him very sober about the realities of labour-management relations even in the alleged ‘golden age’ of capitalism.

For Bob, his personal standing with the media, business and the government was a tactical asset not to be dismissed, but secondary to what was right for Canadian workers. However popular he was in the media, Bob knew full well that it could also be a trap if it seduced you. And it could also change abruptly if your pursuit of justice for workers crossed certain boundaries. Some saw Bob’s iconic status in the media as a boon for the labour movement as a whole and this was certainly true in part. But the larger truth was that Bob was generally seen as an exception rather than a representative labour leader, a plus for the autoworkers and the causes Bob championed, but not a change in the wider perception of unions and working people.

For Bob, his personal standing with the media, business and the government was a tactical asset not to be dismissed, but secondary to what was right for Canadian workers. However popular he was in the media, Bob knew full well that it could also be a trap if it seduced you. And it could also change abruptly if your pursuit of justice for workers crossed certain boundaries. Some saw Bob’s iconic status in the media as a boon for the labour movement as a whole and this was certainly true in part. But the larger truth was that Bob was generally seen as an exception rather than a representative labour leader, a plus for the autoworkers and the causes Bob championed, but not a change in the wider perception of unions and working people.

Bob didn’t romanticize workers but neither did he patronize them. He often noted that when workers were on strike ‘they become philosophers’. What he was getting at was that with the respite from deadening work, and time with their fellow workers away from the machines and clatter, workers proudly passed around pictures of their families, shared their life stories and frustrations, talked about what they would have liked to do and become, and confessed to the shrinking likelihood of realizing those dreams.

Bob himself, as a worker who was comfortable confronting CEOs, prime ministers, premiers and cabinet officials over their policies, was a prime example of the potentials of workers. ‘If a grade-school drop-out like me can do it’, he often said, ‘why not other workers if given the chance like I was?’ Whether or not Bob was just being modest, it captured a great and tragic truth about capitalist society: its disregard and denial of workers’ potentials for having a richer role in society.

Bob had a particular style of leadership. In a telling moment at a Massey Hall benefit for the Fleck strikers, immediately after he became the leader of the union, Bob came on stage, thanked everyone for coming, raised his fist in solidarity and – in deference to the importance of the strike to the women’s movement – turned the event over to Madeleine Parent. Madeleine was a long-time union organizer and feminist, but the significance of the gesture lay in the fact that Madeleine was a co-founder of the left-nationalist Confederation of Canadian Unions which the mainstream labour movement considered a sworn enemy, never to darken any of their functions.

In the early 80s, a rash of plant closures threatened not just a cyclical threat but a new era in worker insecurity. At the CAW Council, as delegate after delegate stood up to tell their depressing story, White quietly listened. As the frustrations grew in anger he calmly took the mike and simply stated ‘I think you all know what has to be done’. No editorializing, no instructions, no unnecessary speechifying. Workers left the council plotting a response and within days, plants were taken over in Windsor, Oshawa and Ottawa.

Those takeovers didn’t reverse the trend, but they led to modest modifications in plant closure legislation and confirmed that workers had only one institution to depend on, their union. (White stayed away from the takeovers for the first few days so the news would have to rely on affected workers, rather than a union official, talking about how their lives had been turned upside down by the closures.)

Soon after, two-tier wages spread from the U.S. airline industry to the U.S. aerospace industry and from there McDonnell Douglas tried to bring this to the negotiations in Canada. Bob angrily labelled two-tier wages a ‘cancer’ and declared that it had to be stopped ‘before it spread into Canada’. And though the union accepted an 18 month grow-in to the top wage, two tiers were effectively stopped, at least until the period following the financial crisis of 2007-2009.

Above all, Bob instinctively reacted to the nature of the times and grew in stature as he led the union through its minefields. It was increasingly state policies in Canada on free trade, taxes, jobs and social programs that affected Canadian workers, not their bargaining ties to the Americans. This placed a premium on working class unity and the development of community ties within Canada.

It was in this period that Bob White grew from an important trade union leader to a charismatic social and political leader. The fight against NAFTA revealed a dramatic shift in the traditional roles of the labour movement and the NDP, its political arm. Now it was the trade union movement and its social allies leading the most important political fight in the country. And Bob, fresh from the national credentials he had achieved in the fight for a Canadian union, served as a key spokesperson for the anti-NAFTA side.

Bob did lose his temper on rare occasions but he quite generally acted with grace, not bluster, and even with a certain impishness. He once came back from a meeting with management and solemnly announced to the bargaining committee that he had some good news and bad news. The bad news was that he had accepted the need for concessions. As the stunned committee froze, wondering what the good news could conceivably be, he added, ‘but I was able to convince them to make it retroactive’. (Bob could only maintain his straight face for another two seconds before he, followed by the committee, broke into roaring laughter).

Bob did as well have his fights with other unions over CAW raiding. But that was inseparable from supporting other workers who democratically expressed their will – as the now-CAW workers had done – over choosing another union to represent them. However controversial this was, it didn’t block a consensus among the Canadian labour movement’s leadership around Bob becoming the head of the CLC (1992-1999) when he retired, nor of Bob working closely with the union heads to lead on issues of racism, gender equality, immigrant rights and international human rights.

No trade union leader can aspire to universal popularity, but the few brushes with other union leaders aside, Bob White came darn close. He was a working class hero when such things were rare and becoming rarer.

Labour Today

We need, however to be cautious of resting our hopes on the arrival of hero-saviors. Bob’s achievements were inseparable from his inheriting a union with a remarkable culture of struggle and supportive structures. His understandings and skills were significantly developed through his interactions with mentors like Tommy McLean (the hard-nosed assistant to the president of the union). McLean identified the potentials of the young Bob White early on, threw him out in the field to get rid of his naiveté and prove himself, and endlessly educated him on the complexities of class struggle and union life.

Moreover Bob came with no magic wand. The victories he led demanded tough work, risky decisions, and sustained education and committed organizing of the members. At the CLC, even though there was progress on Bob’s watch on certain social issues, for all of Bob’s s mediating skills he could not bring the leadership of the unions together to play a more substantive national role on fundamental economic and political issues. This frustrated Bob, but he knew full well that this limit on the CLC was virtually inevitable if the affiliates weren’t ready to both move in new directions themselves and surrender some autonomy so as to facilitate coordinated national actions.

Unions today are in crisis – deep crisis – and waiting for heroes won’t bail them out. A first step is an honest acknowledgement of the depth of this crisis, not only here but across the capitalist world. The second is to confront the radical rethinking this implies about the

orientation of unions, their structures and their relation to their members. To use Bob’s legacy to ignore this challenge and so confirm labour’s status quo is to betray that legacy.

The successes Bob was part of include rich and important clues to a way forward but we will not find answers there. The story of Bob White will only provide a living legacy if it inspires workers and unions to draw on elements of his achievements to figure out anew how, in this particular era, unions can once again mobilize their members and their communities and lead the more general struggles for equality, justice, solidarity and a more meaningful democracy.

The challenge of Bob White’s legacy is therefore how the movement he joined and led might be renewed to deal with a more dangerous world. •

Sam Gindin was an assistant to Bob White when he was CAW president, research director of the Canadian Auto Workers from 1974–2000. He is the author of The Canadian Auto Workers: The Birth and Transformation of a Union.