Free Transit and Movement Building

The demonstrations surrounding the G20 summit in Toronto unfolded more or less as scripted. The state spent obscene amounts of public money to install security cameras in Toronto’s streets, build an enormous fence, and augment the capacities of the local, provincial, and national police forces, both logistically and legally. Demonstrators marched peacefully along a designated route through deserted downtown streets. A few people broke windows and set fire to abandoned police cars. Police made full use of their brand new riot gear and special legal powers. Steve Paiken of TVO was shocked, shocked, to see police aggression directed at journalists and, as he put it, “middle class people” peacefully assembling. A thousand arrests. Denunciations of police lawlessness and brutality. Calls for a public inquiry. Denunciations of vandalism. Calls for solidarity. And of course, the perennial lament that the voices and messages of labour and civil society were lost in the clamor.

To say the events were scripted is not to say that the violence and rights violations were not serious, or that people’s anger, shock, and frustration are not real, righteous, and deeply felt. The problem with this script is that our side loses. We get bogged down in the postmortem, denouncing each other, and then denouncing the denouncers. We pour scarce resources of time and money into mobilizing for legal defense: we are literally put on the defensive. We react with renewed outrage to the predictable “over-reaction” of the state and continue to mourn the movements we should be working to build.

The aftermath of the G20 summit will be an important test for a newly formed activist organization called the Greater Toronto Workers’ Assembly. Formally convened in January 2010, the Assembly is comprised of individual members from a diverse array of unions, leftist political groups, and grassroots community organizations [see list of members’ organizational affiliations]. The Assembly’s organizational culture is still very much a work in progress, and it has not yet proven its capacity to sustain over the long haul the diligent, principled non-sectarianism that it has begun to cultivate over the past year. But coming out of the G20 summit, the analysis and political ambitions that have driven the Assembly’s formation seem all the more urgent and necessary.

Changing the Script

The impetus behind the Assembly, as I see it, is the idea that “changing the script” will require a new form of organization, one deliberately geared to gain traction against the contours of contemporary capitalism. At a time when unions have largely stopped acting like organs of a labour movement, and when workers increasingly identify their own fate with the fate of capital (and not without reason, given the financialization of many pensions), we need an organization capable of confronting the specific ways in which neoliberalism divides, demobilizes, and demoralizes its potential opponents. Since joining the Workers’ Assembly, I have often been asked about the use of the word “worker” in the organization’s name. My answer has been that the work of the Assembly is to rebuild the meaning of “working class.” That meaning will not be realized by fiat, and no organizational vision statement, however comprehensive or inclusive, will generate the cultural meanings that give shape and power to political identities. To rebuild the meaning and political potency of working-class identities, we need an organization that will foster sustained relationships and sustained political dialogue – not as a precursor to movement-building, but as an intrinsic feature of the movement itself.

In the weeks since the G20 summit, I have had many conversations debating the need for various organizations to weigh in on the question of property destruction, “diversity of tactics,” and the meaning of solidarity in the face of state repression. Although I was dismayed that broken windows played their part in the G20 drama, it was hard for me to feel that a movement had been discredited, or that the messages of “legitimate protestors” had been undermined. In the absence of a movement with clear ambitions, an ostensibly tactical debate quickly becomes unmoored from strategy and devolves into a discussion of principles – principles of non-violence, solidarity, opposition to police violence, etc. As long as we are neither harnessed by the practicalities of building a mass movement nor oriented toward a vision we really believe we can win, these debates are unlikely to generate productive disagreement and dialogue on the broader left.

Free and Accessible Public Transit Campaign

The Greater Toronto Workers’ Assembly, however, has embarked on a project that has real potential to develop into the kind of movement in which impassioned debates over tactics will be inspiring and energizing, rather than defeatist and moralizing. At its general meeting in April, 2010, the Assembly voted to dedicate significant energy to a campaign for free, fully accessible public transit in the city of Toronto. Many of our members have been inspired by recent efforts to elaborate the “right to the city” as a rubric organizing demands for public services and city infrastructure (Harvey, 2008; World Charter on the Right to the City, 2004). In Toronto, recent fare-hikes, strikes, provincial funding cuts, cancelled or delayed construction projects, insufficient service, piecemeal and inadequate accessibility infrastructure, and public relations debacles have made our transit system the target of considerable public anger, much of which has been channeled into generalized anti-union resentment and calls for privatization. The Assembly began to see a role for itself here – not only to respond to rhetoric pitting transit riders and transit workers against each other, but to popularize an analysis of public goods and an argument for democratic control over city resources.

Mass transit is an essential pillar of Toronto’s public infrastructure, yet its transit system is among the least “public” public systems in the world. Estimated at between 70 and 80 per cent, Toronto’s “fare-box recovery ratio” – the percentage of the system’s operating budget paid for by individual riders at the fare-box – is among the highest in North America and more than doubles that of some other large cities around the world (Toronto Environmental Alliance, 2009; Toronto Board of Trade, 2010). Many other transit systems in comparable cities “recoup” less than half of their operating budgets from fares, relying more heavily on subsidies from multiple levels of government. According to the Toronto Board of Trade (2010), “essentially no North American or European transit systems operate in [the] manner [of Toronto]” with respect to transit funding.

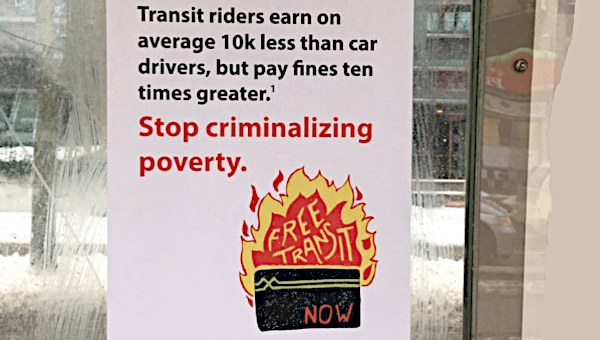

Riders rarely think about rising “fare-box recovery ratios,” but few have failed to notice that fares have increased from $1.10 in 1991 to $3.00 in 2010 – the last fare-hike in January 2010 arriving in the context of high unemployment and rising demand for emergency food and shelter services in the city. The fare-box recovery ratio represents a rough quantification of the efficiency with which neoliberal governments have divested from the public sphere and downloaded costs to the most vulnerable individuals. The failure to invest seriously in mass transit in recent decades has meant, moreover, that many Toronto residents outside the downtown core pay high fares for service that is inconvenient and inefficient. While the operating subsidies that support other transit systems reflect an understanding of mass transit as a public good, yielding benefits to entire communities and ecosystems, Toronto’s system increasingly treats transit as a commodity, consumed and paid for by individual riders. The funding structure of Toronto’s transit system is effectively a form of regressive taxation: although all of Toronto’s residents benefit from transit infrastructure – including the car-owners who never ride a bus – our “public” system is funded disproportionately out of the pockets of the low- and middle-income people who rely on mass transportation in their daily lives.

Anti-Capitalist Politics

The demand for free and accessible public transit has the potential not only to develop into a broad-based movement, but also to drive the development of the new kind of organization that the Assembly aspires to become. The Assembly is committed to its call for the outright abolition of transit fares, not merely a fare-freeze or fare-reduction. What is exciting to me about the free transit campaign is that the expression of a radical anti-capitalist principle – the outright de-commodification of public goods and services – actually serves in this instance to invite rather than foreclose genuine political dialogue about values, tactics, and strategies. While still in its early stages, the free transit campaign is already pushing us to elaborate both analytical and strategic links between commodification, environmental justice, the limits and capacities of public sector unions, and the interlocking forms of exclusion faced by people marginalized by poverty, racism, immigration status, or disability. Free transit could represent a site of convergence between many distinct activist circles in the city and foster greater integration and collaboration between environmental advocacy, anti-poverty work, and diverse human rights organizations. If the free transit campaign does succeed in bringing diverse and distinct activist cultures into conversation with each other, it will force the Assembly to grapple with strategic questions about its relationship to less radical organizations in the city. Given the marginalization and isolation that have long plagued leftist groups in Toronto and elsewhere, this should be a welcome challenge, particularly if the Assembly hopes to become an effective left pole in a broad alliance.

Among the strengths of the free transit campaign is the concreteness of vision. Within the left, efforts to elaborate a broad anti-capitalist vision too often run aground at the level of abstractions, generalities, and platitudes. Most Toronto residents would draw a blank if asked to “imagine a world without capitalism,” but what Torontonian who has ever waited for a bus can’t begin to imagine an alternate future for the city, built on the backbone of a fully public mass transit system? The invitation to imagine free transit is an invitation for transit riders to imagine themselves not simply as consumers of a commodity, but as members of a public entitled to participate in conversations about the kind of city they want to live in. Without devolving into abstract and alienating debates over the meaning of, say, socialism, the call for free transit invokes the things we value: vibrant neighbourhoods; clean air and water; participatory politics; equitable distribution of resources; public space where we are free to speak, gather, play, create, and organize. Even the most skeptical response to the idea of free transit – “how will you fund it?” – is the opening of a productive conversation about taxation and control over public resources. The call for free transit can effectively open a space for an unscripted political dialogue about the meaning of fair taxation, public goods, collective priorities, and public accountability for resource allocation.

But perhaps more fundamentally, the free transit campaign is a rare example of a political project on the left that is not reactive, defensive, nostalgic, or alarmist, but hopeful, proactive, and forward-looking. “Crisis talk” is pervasive in much of contemporary culture, but in left circles, it has become difficult to imagine a mode of organizing that is not oriented around predicting or responding to punctuated calamities of various kinds – whether a financial meltdown, an un/natural disaster, the latest wave of layoffs and service cuts, or the systematic violation of basic civil liberties on a weekend in downtown Toronto. In the case of free transit, however, we are free to move ahead with the campaign on our own timeline, to seek out and develop the kinds of relationships and democratic spaces that are necessary to sustain grassroots movements over the long term. For the Assembly, this will mean having the space and time to realistically assess its own capacities and to organically develop its own strategies and priorities.

The Assembly does not have modest ambitions: it hopes to nurture a broad-based anti-capitalist movement and to vitalize a new working-class politics (Rosenfeld and Fanelli, 2010; Dealy, 2010). Its members are, I think, tired of listening to militant rhetoric unanchored to any genuine hope of winning. The push for an excellent, fully public and accessible transit system is a radical demand with immense popular appeal, an ambitious, long-range goal for which clear, achievable interim political victories are possible along the way. Free transit is not a crazy idea. Arguments in favour of free transit have surfaced sporadically in Toronto over the years, whether in an editorial by CAW economist Jim Stanford in The Globe and Mail or in a CBC interview with Deborah Cowen, a professor of geography at the University of Toronto (Stanford, 2005; Cowen, 2010). Some cities already have free transit systems, and many have partially free systems – in the downtown core, during holiday seasons or off-peak hours, or on “spare the air” days when smog levels are high. But in Toronto there has not yet been an initiative focused on building a broad-based movement dedicated to the eventual abolition of transit fares in the name of social, economic, and environmental justice.

Baby Steps

Without abandoning or compromising its radicalism, the Assembly can push for concrete steps in the direction of de-commodified transit and build productive relationships with individuals and organizations who do not necessarily identify themselves as anti-capitalist. It will be in the process of pushing for interim reforms along the way to a de-commodified transit system that the Assembly will most need to articulate its political principles and its analysis of the spatialization of race and class in Toronto. Free transit in the downtown core may, for instance, be good for Toronto’s tourism industry, but will it benefit the immigrant and working-class communities in transit-poor areas of the inner suburbs, who spend proportionately more of their income to access poorer quality services than those available downtown? Proposals to pay for free transit through suburban road tolls will similarly hit hardest those working-class communities whose neighbourhoods are so underserved by transit that they have no choice but to drive into the city for work. The process of developing interim priorities will not, in other words, postpone the challenge of articulating and popularizing a class-based and anti-racist argument for public infrastructure. Instead, the Assembly will be forced to pursue its most radical aspirations by cultivating a sustained dialogue about the interim remedies and strategies that will both address real needs in our communities and help build a broad-based movement over the long term.

It will be through this process of dialogue, I hope, that a new articulation of a politicized working-class identity might emerge. Our earliest discussions of the free transit campaign are already pushing us to think about the social complexities that will need to be navigated if we are to build an effective free transit movement. Success will depend on our capacity to carve out and sustain a space for dialogue and negotiation among transit workers and riders, within unions, and across neighbourhoods and communities that have been unevenly affected by fare hikes and inadequate services. Questions of tactics and strategy cannot be divorced from the process of identifying, developing, and strengthening the complex connections between the people who need and use public goods and services and the workers who provide them. We will need to recognize the different ways in which our various constituencies are powerful and vulnerable and learn how to defend and protect each other. The free transit campaign lends itself to the kind of intensely local organizing through which honest dialogue, trust, and long-term relationships can be developed and nurtured – within and across neighbourhoods and among transit riders and workers. And of course, without these things, the campaign will go nowhere.

Among the strengths of the free transit campaign is its potential to foreground and develop an analysis of our collective stake in the protection of public goods. It is not difficult to talk about public goods in the context of mass transportation infrastructure. The shared benefits of public transportation are difficult to deny, particularly in a city as large and as sprawling as Toronto. Even setting aside the obvious ecological imperatives that should be driving public investment in greener infrastructure, there are powerful economic reasons to support a massive re-investment in Ontario’s transportation sector. A serious effort to expand the reach and accessibility of the public transit system would serve not only to ease the burden of Toronto’s most vulnerable residents and reduce the economic and health costs associated with air pollution and traffic congestion: such an investment could re-direct the wasted skills and resources embodied in Ontario’s laid-off auto-workers and silent auto-plants, which could be converted to the production of high efficiency mass transit vehicles. As Sam Gindin and Leo Panitch (2010) argued recently in the Toronto Star, public borrowing to finance such investments represents not a wasteful burden on future generations, but a commitment to securing them a future. The real squandering of our collective resources lies not in public borrowing or in benefits packages for public employees, but in our failure to direct existing skills, knowledge, and material capacities into a coherent strategy for building sustainable communities.

The idea of a free transit movement immediately foregrounds a number of thorny strategic questions for the left in Toronto: how to build trust, dialogue, and support for a free transit movement within the transit union; how to address and re-focus the widespread anger, mistrust, and resentment directed at the public sector in the current climate; how to sustain and advance anti-capitalist principles while building productive relationships within broader progressive milieux. Navigating these questions will be challenging, and the Assembly is still a long way from a coherent and systematic approach to answering them. But the fact that these questions surface so quickly and urgently is a positive sign of the ambition and seriousness with which the Assembly is approaching the organization of a free transit movement. The free transit campaign will push the Assembly to develop further its internal organizational and decision-making capacities, but it will also demand an outward-looking, inclusive process, in which the Assembly’s role is to open space for debate, dialogue, and collective strategizing.

In fact, the transit system itself can provide the venue for us to stage public discussions about our collective resources and to share alternative visions for our city: the transit system is a readymade classroom, theatre, and art gallery, attended every day by people who could come to recognize their stake in the de-commodification of public goods of many kinds. My hope is that Toronto’s buses, streetcars, and subway platforms could be places for experimentation, places to develop the new tactics, organizing skills, and relationships that might permit us to really depart from the prevailing script. •

This article first published in Alternate Routes.

References:

- Averill L. (2010). Drivers and Riders Unite! Bullet, No. 424.

- Dealy W. (2010). The Greater Toronto Workers’ Assembly: Building a Space of Solidarity, Resistance, Change. Relay, 30, 27-28.

- Gindin S, and L. Panitch. Public Sector Austerity Unreasonable and Irrational. Toronto Star. Retrieved on August 25, 2010.

- Greater Toronto Workers’ Assembly. Retrieved on September 9, 2010.

- Harvey D. (2008). The Right to the City. New Left Review. 53, 23-40.

- Rosenfeld H, and C. Fanelli. (2010). A New Type of Political Organization? The Greater Toronto Workers’ Assembly. MR Zine: A Project of the Monthly Review Foundation. Retrieved on August 23, 2010.

- Stanford J. (2005). Free Public Transit on the Dirty Brown Horizon? The Globe and Mail. Retrieved on August 12, 2010.

- Toronto Board of Trade. (2010). The Move Ahead: Funding ‘The Big Move’. Retrieved on September 12, 2010.

- Toronto Environmental Alliance. (2009). Transit Commission Briefing Note TTC Operating Budget 2010: Fare Increase. Retrieved on September 8, 2010.

- Transit Funding Challenges for Toronto’s Communities – Interview with Deb Cowen. Metro Morning. Canada: Canadian Broadcasting Corporation March 29, 2010: runtime 8:03.

- World Charter on the Right to the City. (2004). Social Forum of the Americas, Quito, Ecuador. Retrieved on September 12, 2010.

- Free Transit links.