No Fare is Fair

A Roundtable with Members of the Greater Toronto Workers’ Assembly Transit Committee

The Greater Toronto Workers’ Assembly (GTWA) is a promising new initiative aiming to build a united, non-sectarian, and militant anti-capitalist movement in the city among a diversity of rank-and-file labour unionists, grassroots community organizers, and youth alike. Since the GTWA’s inception in early 2010, mass public transit has emerged as one of the organization’s key political battlegrounds. In this in-depth roundtable discussion, members of the GTWA’s transit committee Jordy Cummings, Lisa Leinveer, Leo Panitch, Kamilla Pietrzyk, and Herman Rosenfeld explore both the opportunities and obstacles facing the campaign Towards a Free and Accessible TTC.

Ali Mustafa (AM): Towards a Free and Accessible TTC became the first major campaign adopted by the GTWA. Why is mass public transit a key priority to the work and overall vision of the GTWA?

Herman Rosenfeld: Actually, it took about two assemblies before we endorsed this campaign. We took some time to evaluate different possible campaigns and, after that, we decided to choose transit as a priority. All working people – all people, really – should have the right to mobility and shouldn’t have to pay for it like any commodity. It should also be accessible to all people and not doled out according to how much money you have, which part of the city you happen to live in, or whether or not you are living with a disability. If we want to politicize people by putting forward a vision of a different kind of society, free and accessible transit has to be a part of that strategy.

The campaign also poses a vision of public transit that is ‘non-commodified’ – that is, not something that is bought or sold in the marketplace but exists as a service and public good that is not owned or managed by private business interests seeking to make a profit. A similar vision motivated people to create public Medicare in Canada. In mobilizing people and doing education around the need to make public transit a right that is accessible and fare-free, this campaign forces us to address current attitudes about taxes, public-sector spending, and austerity by not only understanding them but challenging the legitimacy of the neoliberal ideas behind them.

Jordy Cummings: The GTWA is a new kind of political organization, in recognition of the limitations of the past. One of the ways we can open up space for an anti-capitalist vision that is shared by diverse elements of the Left is to start with something deceptively simple like free and accessible transit, and from there you begin to get an entire vision of a de-commodified social order. It’s not just a ‘single issue’ campaign; it’s a campaign that fundamentally challenges capitalist social relations from a working class, transit-using standpoint.

But what about those who live in the outlying regions of Toronto who are either forced to buy private automobiles or take ninety minutes or more to get to work because of the poorly planned transit routes? Most people in Toronto use transit every day to go to work and come home, so fighting for free and accessible transit is a fundamental issue to address a broader anti-capitalist vision overall.

Kamilla Pietrzyk: This campaign also arose in part from the energies around the Right to the City campaign and the recognition that organizing around the issue of transit can have great popular appeal right now because so many residents of Toronto are upset about the recent fare-hikes. While transit systems in other large metropolitan areas get large government subsidies to cover their costs, Toronto’s transit system relies on user fees for approximately 70 per cent of its operating budget, causing fares to rise to $3.00 in 2010. As a result, there has been a lot of dissatisfaction regarding the state of transit in the city. We believe that by building an effective campaign around free and accessible transit, we can direct that anger and frustration around fare-hikes to include an analysis of public goods, public accountability, the failures of the market system, and the right to democratic participation in the shaping of our city. A free transit campaign has the potential to be a popular movement because it has clear and tangible links to the daily experiences of many people, especially those with low income.

AM: What type of groundwork has been done to date by the GTWA transit committee to help build the campaign across the city – including any education, outreach, and public events – and what has been the general response to these efforts thus far?

Kamilla Pietrzyk: So far we have organized a number of large public events and held a series of smaller flyering actions at major TTC stations. The larger events include a public forum on Free and Accessible TTC in July 2010, which involved a number of speakers from transit-related groups and initiatives. We also held a street party in Christie Pits Park in October 2010, which was the official launch of the campaign and featured speakers, musical performances, food, and general festivities. Both of these events were successful in stimulating further debate around transit issues in Toronto and mobilizing new support for the campaign. Our more mundane organizing has focused on engaging with people at TTC stations, giving out pamphlets and talking to them about transit in Toronto. The response from the public has been very supportive. The vast majority think that free and accessible transit is a tremendous idea; their only reservation tends to be around the question of how to fund it. But even on this point, many of them become sympathetic once they find out that for the $1-billion wasted on security during the G20 summit in Toronto last summer, we could have enjoyed free transit for a full year.

We intend to continue our public outreach work through ongoing flyering efforts. We have also been inspired by the popularity of the Bad Hotel Youtube video, where a group of activists infiltrated Westin St. Francis hotel in San Francisco and performed an adaptation of Lady Gaga’s song Bad Romance in support of the workers’ struggle to secure a fair contract. We recently developed a set of Guerrilla theatre scripts to be performed in conjunction with the GTWA’s cultural committee on streetcars, buses, and subways.

AM: Are you linked in any way yet with other groups in the city also campaigning around the issue of mass public transit (fare-free seeking or not) in order to build a ‘broad-based movement’ on this front?

Herman Rosenfeld: We have organized joint events with DAMN 2025, a group working for full accessibility of public transit and people living with disabilities; and Sistering, who have been agitating for lower fares. Surprisingly, there aren’t all that many movements dealing with fare issues.

AM: What do you have to say to those who argue that free and accessible mass transit is a wonderful idea in principle but in reality too unrealistic or impractical, especially during a major period of recession?

Jordy Cummings: That’s not an easy question to answer, but we do need to take free and accessible transit as a first principle. On a concrete level, given the amount of money the state (let alone private markets) spend on jails, the G20 Summit security budget, and military armaments, there is certainly enough money available for free and accessible transit to become a reality. But there is also immense pressure for austerity in the other direction.

As a union activist, I learned that you need to demand more than you think you’re going to get, so fighting austerity by merely demanding that the status quo is maintained isn’t going to cut it. ‘Be realistic, demand the impossible,’ as the saying goes.

Lisa Leinveer: I would agree with Jordy, and add that for many people with disabilities and their allies, both fare accessibility and physical accessibility of public transit is a first principle. A physically accessible transit system is not an extravagant accommodation. Not having an accessible transit system is a form of social segregation. For many people in Toronto, transit is the only option to get from one place to another across the city, and yet close to 30 per cent of TTC bus routes, 50 per cent of subway stations, and 100 per cent of streetcars are totally physically inaccessible. Transit is a public good; it should be accessible to all the people of a city.

Herman Rosenfeld: For the powers that run this city and country – and the business community in general – this will never be practical or desirable, recession or not. But it does challenge many basic assumptions of living under neoliberalism: there isn’t enough money to go around and pay for transit as a social service; the current recession requires austerity, rather than expanding public services; taxes are already too high, so we have to shrink the size of government, and so on. These notions need to be challenged as part of a political and ideological assault on the ‘common sense’ of this era of capitalism. Fighting for free and accessible transit forces us to do so.

In another way, we also need to fight for shorter-term reforms that can give us confidence for ultimately demanding more expansive goals. We can call for cuts to current fares, dramatic increases in the levels of service, and democratic control over the larger planning processes – this would allow us to hone in on specific ways of increasing services for particular communities and build a base for a larger campaign. Of course, even raising these rather short-term demands also requires us to respond to the same set of concerns that people raise about the longer-term ones.

Leo Panitch: Everything from schools to libraries to healthcare to water services is paid for by tax revenue. Roads don’t have user fees – why should public transit? We can pay for free transit through a fair tax system. The amount of taxes that riders would have to pay for fare-free transit would be much lower than the amount that they spend each year on the cost of commuting. Even those who drive cars are prepared to pay taxes for less traffic – and there is no better way to do this than by expanded and free public transit. Harper’s government is spending money on building new prisons and buying the military new fighter planes for $35-billion for no useful purpose. All sorts of tax breaks are given to the oil and gas industry as it threatens our environment. Is this how we want our taxes spent? We need to make our tax dollars benefit the common good and make our governments provide fare-free transit!

AM: Since former Premier of Ontario Mike Harris saw all provincial and federal subsidies to the TTC cut in 1996, the TTC’s financial viability has been entirely dependent on municipal funding and user fees (the latter comprising 70 per cent of the revenue base). Assuming increased property taxes alone cannot make up the shortfall, how exactly do you envision the project for free TTC service being funded?

Herman Rosenfeld: Harris didn’t cut federal subsidies – that was the result of the abandonment of city life by the Liberal and Conservative governments of Chretien, Martin and Harper. Public transit should be funded by a combination of municipal taxes, federal and provincial funding, and contributions through driver tolls. Property taxes are unfair and limited. Cities like Toronto need new sources of taxation, such as a city income tax. The rates for federal and provincial income taxes can be made fair by lowering them on the bottom-end and increasing them for large, wealthy corporations, as well as those that receive huge bonuses in the financial sector.

Most importantly, the needs of people in cities must become a priority of state financing – this is a question of priorities between giving subsidies to private capital in the hope that wealthy investors will be bribed into creating low-paying jobs, or using the resources created by working people to serve our collective needs and, in the process, creating high-paying, secure, and environmentally friendly employment.

Capital costs (building new lines and infrastructure) can be financed through bond issues, which is another way for describing borrowing on international bond markets. The possibilities of doing this are dependent on the belief that we can pay those bonds back over time through revenues derived by tax dollars, and the new economic activity that a massive new transit system would create.

Leo Panitch: The transportation sector that is so central to Ontario’s whole economy is in crisis. This crisis is obvious from auto industry shutdowns and layoffs and the notorious traffic congestion on our roads. We need to change the old car plants so people get jobs producing the mass transit vehicles needed for a free and accessible public transit system. Just as the original subways, and the street cars and buses too, were funded by issuing Ontario bonds, so can this be done today. The very low interest rates make it less costly to do this than ever before, while the new jobs provided will expand the tax base. Far from placing a burden on future generations, this would guarantee them a future. And we also need to be able to rely on our banks to direct funds to shifting the whole transportation sector toward public transit. The money we put in our banking system should be used to meet our society’s real needs.

It’s time for a wider vision for our city. Free public transit will help create the healthier, cleaner and better integrated neighbourhoods we all want. And rather than pitting public transit workers against riders, it will help create a public transit community committed to excellent service and accessibility for all. We all want more and better public transit, less road traffic, fewer accidents, cleaner air and greater mobility.

AM: Your campaign material sites several cities across North America currently operating under zero user-fees, including Commerce, California; Chapel Hill, North Carolina; and Coral Gables, Florida. But since all of these cities are significantly smaller in size than Toronto, is it possible that Toronto is simply too large for this kind of project to be feasible?

Herman Rosenfeld: I think this reflects the political difficulties of getting this kind of project on the public agenda in big cities, rather than any technical or other obstacles. Cities are the center of neoliberal economies, particularly with the dominance of finance and private-sector development in major urban centres. This kind of campaign challenges the nature of how those places are organized and structured, which is why they seem so difficult to move on. Smaller centres that are geared around colleges or tourism don’t present the same challenges.

Lisa Leinveer: We can also learn much about how accessible transit can be done by looking to examples of other transit systems in the world. Many newer transit systems are far more accessible. A study of different transit technologies globally yields many innovative approaches to transit that prioritize physical access and green technology; among these are Curitiba’s high-speed accessible bus system, and variations on the Light Rail Transit (LRT) system that was proposed in Toronto and has been implemented in many cities around the world. Although no system is perfect, the successes and limitations of various systems can guide our fight to make transit free and accessible here in Toronto. When overall access is not made a fundamental priority, it is a reflection of the deeply ableist and elitist priorities of the government.

AM: The Bus Riders Union (BRU) in Los Angeles is perhaps the most successful example in North America of a working class movement built around the issue of mass public transit, yet even they have avoided calling for fare-free transit. Why is the GTWA transit committee seeking free TTC service, and not merely a cheaper or more affordable option?

Jordy Cummings: We have discussed incremental demands within the spirit of ‘Free and Accessible Transit.’ One slogan recently proposed has been ‘Cut Fares, Not Services.’ Speaking for myself, I’d again drive home the point that demanding lower fares won’t get lower fares. Saying ‘No Fare is Fair’ is more likely to create an impetus for lower fares.

Herman Rosenfeld: There is nothing wrong in raising or fighting for lower fares and greater levels of service and accessibility than we have today – that is different than giving up on the fundamental goals of this campaign. The BRU is based on building an organizational power-base among bus riders in order to increase the accessibility and availability of bus service in Los Angeles. In other ways, its goals are similar to ours: allowing working people to access public transit; protecting the environment; and acting to organize workers in communities as a way to build a movement against the logic of private market accumulation.

AM: Why is ‘accessibility’ in particular a key demand of the campaign, and what do you see as some of the glaring failures currently characterizing TTC service in this regard?

Kamilla Pietrzyk: If we are serious about improving transit accessibility, then saving Transit City is not enough. We need to demand better, safer, more accessible transit. We also need a commitment to improving and expanding existing transit infrastructure, so that people from communities outside the downtown core like Markham, Scarborough, or North York can enjoy adequate transit services. Huge portions of the city are virtually inaccessible because there are no accessible transit routes nearby. We want all of our transit vehicles and stations fully accessible.

Lisa Leinveer: As I stated earlier, far too many of the bus routes and subway stations are totally physically inaccessible. Repair of any subway stations that actually are accessible has been underprioritized. Many elevators and escalators in subway stations have been out of service for months. For example, the elevator at the Yonge/Bloor station was out of service for nine months before it was finally back in operation on December 16, 2010. As a result, many people could not transfer between the North-South line and the East-West line during this time. These kinds of service delays mean that people who need elevators and escalators cannot use those stations for extended periods of time, further blocking them from accessing some areas of the city. These repairs need to be prioritized, and more stations need to be made accessible in the first place.

Wheel-Trans, the unreliable ‘alternative’ to the TTC, is a segregated and discriminatory system that requires painful and humiliating tests for eligibility. If a person does qualify, they have to plan trips 24-hours in advance, and if they need to call instead of using the Internet, they may spend up to an hour on the phone waiting to get through because there are not enough workers on the line. There is much more demand than supply of Wheel-Trans buses, which means that if a person requests a ride at 2pm, they might be offered one at 4pm, or they might simply be declined. There are many other unfair rules that govern the lives of Wheel-Trans users.

A Wheel-Trans ride might arrive 20 minutes early, or 45 minutes late – without penalty. At the same time, if a rider is not ready within 5 minutes, the driver will leave and they will have missed their ride. If a rider happens to miss a ride four times in a month, they are cut off of Wheel-Trans access for two weeks. People often face discrimination and abuse from drivers working under terrible labour conditions. We also demand improved training and working conditions of Wheel-Trans drivers. We are not calling for the end of Wheel-Trans, since for many people it’s the only way that they access public transit at this point. Rather, we are calling for the whole transit system to be made physically accessible, including all stations, bus routes, and streetcars.

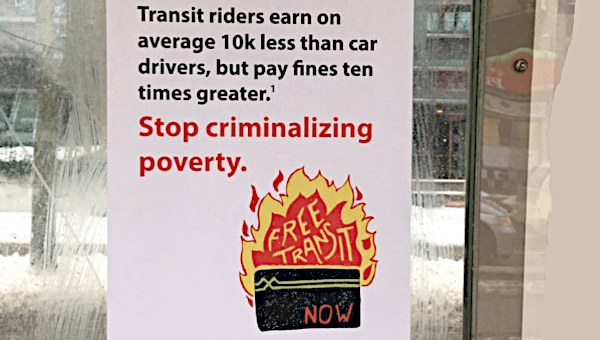

Fare access is also a disability issue. Poverty in general is a disability issue, since poverty and disability are critically linked in the context of capitalist societies like Canada. Transit costs $3 per ride and $6 for a round-trip – if you have attendant care, that goes up to $12 for a round-trip! This is compounded by a political and economic system that keeps many people with disabilities in poverty. We demand free transit for TTC users and their attendants.

AM: Rob Ford, the recently elected Mayor of Toronto, campaigned on an open platform to annul Transit City, and by all appearances seems keen to fulfill his promise. Where does your campaign stand in relation to Transit City, and do you think it is possible to in any way reconcile the two initiatives?

Herman Rosenfeld: Transit City is in reality a series of light rail lines that seeks to include inner suburban neighbourhoods in the larger transit grid; it’s the result of a series of compromises that represent the strengths and weaknesses of the [former Mayor David] Miller era (and previous city and provincial administrations). We tend not to defend all of Transit City but parts of it. As a result, we are not part of the movement that argues that the be-all and end-all of transit policy is the defense of Transit City.

For us, the key is open, democratic planning; a rejection of neoliberal austerity; and opposition to the anti-public transit policy of Ford. We need to consult with people in the affected areas to see what they want and need and try and articulate that message around the concerns of those currently working to defend Transit City.

Lisa Leinveer: To that I would add that although it’s commendable that the LRT system proposed would be accessible, this should not sway us from our critiques of Transit City overall, nor from our goals of changing the infrastructure of existing lines to make them physically accessible.

AM: What is your envisioned relation to the TTC and TTC workers?

Jordy Cummings: Like other public services, the relationship would not change. There is some fear among TTC workers that free transit would mean less jobs, but there’s no reason that those taking tickets or working within finance and other departments cannot be redeployed in a variety of ways to make transit a more affordable and accessible experience.

Recently, Mayor Ford and the ‘liberal’ provincial government recently attempted to make TTC an essential service – this is a slap in the face to TTC workers. While the Amalgamated Transit Union (ATU) cannot publicly back our campaign, TTC workers I’ve encountered have been remarkably receptive to the idea, as have other public and private sector trade unionists.

Lisa Leinveer: Being in solidarity with TTC workers, we believe that systemic change should include the improvement of working conditions for TTC and Wheel-Trans workers. We oppose framing these debates in narrow terms – for example, saying that it’s the fault of the drivers that Wheel-Trans is unreliable. Part of making transit in Toronto less ableist, and therefore more accessible, is the prioritization of anti-ableist training and better working conditions for all TTC staff.

AM: Finally, people will need to begin to believe that fare-free transit is possible before it can happen. What do you currently see as the key obstacle to the campaign becoming something that is seen as attainable in the public consciousness?

Jordy Cummings: The majority of people in Toronto in principle would back the idea of free transit. I think the obstacle is how we’re socialized under capitalism to see things (public and private goods) as commodities, and the entire set of social relations that accompanies this way of thinking. For example, it seems normal for us to pay for some services, yet not for an appointment with our doctor or taking out a library book. What is the difference?

Leo Panitch: Nothing unites the people of the Greater Toronto Area as much as mass public transit, whether it is the TTC or GO Transit. We take it for granted since we use it every day and spend a good portion of our hard-earned money on unfair fares. Why then, is our supposedly ‘public’ transit system among the least public in the world? Our fares pay a large part of transit costs. Since 1991, fares have increased from $1.10 to $3.00 in 2010. And fares will likely continue to increase $0.25 each year. Why should we stand for this? Transit systems in other cities get more government funding to cover their costs. Other cities in the world put money into mass transit because people demand that the comfort, safety and cost of their commute is part of the common good. We Canadians are proud that we have a Medicare system that means we don’t have to pay for each time we go to the doctor or a hospital. We don’t have to pay a fee for water each time we turn on the tap or flush the toilet. We know that a public education system means our children don’t have to pay to go to school. We got these things because people came together and demanded them and won them from governments. A fare-free and accessible TTC is possible, if we demand it. •

To contact or get involved with the GTWA transit committee:

- Email: nofareisfair@gmail.com

- Blog: gtwanofareisfair.blogspot.com

- Tumblr: nofareisfairgtwa.tumblr.com

- Web: www.freetransittoronto.org

- Facebook: www.facebook.com/groups/nofareisfair

- Twitter: @nofareisfair

- Twitter: @freetransitTO