Learning from QuAIA’s Experience: Why Free Speech Matters

In 2009, Queers Against Israeli Apartheid (QuAIA) kicked off the annual Pride season in Toronto with a public meeting about the continuities of queer solidarity organizing – from the Simon Nkodi Anti-Apartheid Committee in the 1980s to QuAIA’s work against apartheid in Israel/Palestine today.

Then the shit started hitting the fan.

Anyone who has dared criticize Israel’s illegal occupation of Palestine or its apartheid system has become used to a histrionic response. But QuAIA’s meeting was introduced by El-Farouk Khaki, who had earlier been chosen as Grand Marshal for Pride 2009. Khaki is also a Muslim. The attacks were especially over the top. B’nai Brith’s Executive Vice President Frank Dimant described him as “part and parcel of the anti-Israel machinery that continues to churn out hateful and divisive propaganda,” and demanded that he be removed as Grand Marshal. Further, Dimant and other voices from the Israel lobby demanded that Pride ban QuAIA from the parade as a hate group.

Ultimately, the campaign to have Khaki removed as grand marshal and QuAIA barred did not succeed. A major problem was that their main spokesperson, Frank Dimant, is not only straight, but also keeps some very homophobic company. He moonlights as professor of Israel studies at the Canada Christian College, a fundamentalist training camp run by Charles McVety. Many people consider McVety to be Canada’s leading homophobe. He (unsuccessfully) led the charge against gay marriage, and more recently (successfully) pressured the Ontario government to deep-six its new sex-ed curriculum. He also brags about his close connections with Stephen Harper.

QuAIA Victorious, But Attacks Continue

QuAIA marched without major incident, but the Israel lobby did not go away. Martin Gladstone, a gay estate lawyer, shadowed the 2009 QuAIA contingent with a video camera and produced a crude propaganda piece that tried to portray the group as a gang of dangerous neo-Nazis who had infiltrated Pride.

The lobby’s target also changed. Their sights were now aimed not so much at QuAIA as at Pride Toronto, the group who organizes the festival and who had refused to ban QuAIA from the parade. The lobby targeted Pride where it was most vulnerable – funding. Gladstone distributed his video to all city councilors. Secret meetings took place between city staff and pro-Israel lobbyists who demanded that the city cut all support for Pride unless anti-Israel messages were banned in 2010. The lobby contacted corporate sponsors with similar demands.

By the spring of 2010 there was intense pressure on Pride. On April 19, the Toronto Star published a half-page story entitled, “Dispute threatens funding for Pride: Queers Against Israeli Apartheid violated policy, city says.” It quoted the city’s general manager of economic development and culture, Mike Williams, as saying that the city “believes its anti-discrimination policy was likely violated by QuAIA’s conduct and even its very presence at last summer’s parade.” On April 28 city councilor Giorgio Mammoliti issued an ultimatum that he would introduce a motion that the city withdraw all funding from Pride unless it moved to ban QuAIA.

Under the direction of an executive director with no roots in the community, the weak and politically inexperienced Pride board gave in, deciding by a one vote margin to ban QuAIA from participating.

The community response was immediate and dramatic. The Pride Coalition for Free Speech (PCFS) was formed. May 21, a crowd of 100 demonstrated outside the morning press conference where Pride announced the banning. A few days later, 2010 Pride Grand Marshal, Alan Li and Honoured Dyke Jane Farrow refused to accept their positions. The co-chairs of the International Lesbian and Gay Association, invited to be the international grand marshals, likewise refused to take part. Twenty-three former Pride honorees returned their awards and presented the organization with an “Award of Shame.” Blackness Yes, organizers of the perennially popular Blockorama, already furious with the pride board over its high handed treatment of the Black and Caribbean communities, expressed its solidarity. So did trans community members. A number of women organized Take Back the Dyke, an alternative to the official Dyke March, in protest.

After a month of controversy, a group of “community elders” came up with a last-minute face-saving strategy. On June 24, Pride rescinded its banning of QuAIA. All participating groups were to sign an undertaking to respect the city’s anti-discrimination policy. QuAIA marched with its biggest contingent ever, together with its allies in the Pride Coalition for Free Speech.

The Question of “Free Speech”

It would be fair to say that internally QuAIA was slow to recognize the importance of free speech as a basis of unity in this struggle. Several members expressed anxiety that free speech arguments were a “liberal” diversion that pulled us off our message of Palestine solidarity and the campaign for boycott, divestment and sanctions (BDS) against Israel. They expressed discomfort with the fact that many of those who were supporting our right to be in the parade were not particularly onside with our message about Palestine and Israeli apartheid.

As the struggle developed, however, it became more and more evident that the basis of unity around free speech was responsible for producing a constellation of forces that actually amplified and legitimated our message in the community.

Struggles around freedom of speech are built into the DNA of the queer community. My first demonstration as an out gay man was in 1974 against the Toronto Star, which at the time was refusing to accept classified ads containing the word “gay.” Then there were fights to get community publications included in libraries. We took on the Ontario Censor Board when it banned queer sexuality from movies. We fought charges of obscenity against the gay liberation magazine, The Body Politic. There were years of legal challenges against Canada Customs regulations that prohibited the importation of LGBTQ-themed books. We overturned the ban against queer speakers in the public school system.

We won those fights because “free speech” is a hegemonic democratic value. This enabled us to solicit support from significant sectors outside the community, even those who were not initially comfortable with queer content. Through those struggles we built relationships, educated people about the substantive issues, and moved those issues – and our communities – from the periphery to the centre of popular discourse.

I would argue that our experience in the struggle around Pride in 2010 demonstrated that the same principle holds for the Palestine solidarity movement today.

Building Bridges

Before the events around Pride, it would be fair to say that many people in Toronto’s network of queer communities knew very little about the notion of Israeli apartheid or, if they did, wouldn’t have considered it to be any kind of a queer issue. Because of the controversy about our right to participate in Pride, however, the term “Israeli apartheid” became a household word in the community. For months the name of our organization featured prominently in both community and mainstream media. The issue was the topic of thousands of conversations. Riding on the wave of support for our right to be in Pride, the notion that Israel could be an apartheid state was no longer a marginal issue.

This movement took place because a host of people with real weight in the community (and whose opinions on Israel/Palestine were all over the map) were able to agree that banning us was unacceptable. And by working with and building relationships with those people, we both normalized talking about Israeli apartheid and discredited the Israel lobby’s silencing campaign. We challenged the notion that criticism of Israeli policies was anti-Semitic or hateful.

Instead of seeing the debate about freedom of speech as a detour from our message about Israel/Palestine, we made it a bridge to bring that message to a much broader community.

But crossing a bridge doesn’t mean that a journey is over. It would be wrong to suggest that a simple familiarity with the term “Israeli apartheid” is the same as a nuanced understanding of the issues involved. Such a familiarity, however, is a necessary first step in the process of coming to that understanding.

Months after Pride Week, for example, I unexpectedly found myself dealing with the issue of Israeli apartheid in a workshop about the early AIDS movement. Several participants had seen in the press that I had been associated with the controversy around Pride, and spontaneously asked me about it. Most of that group was starting from zero knowledge. We ended up finding a map of the world to help locate Palestine and Israel. (We should never underestimate at what basic level we need to begin.) Without the battle about our right to participate in Pride, that conversation would never have happened.

The struggle was also an educational process for many of our allies. A year before the 2010 banning controversy I had a conversation with an acquaintance who had pretty much bought the Brand Israel narrative about the country being an oasis of tolerance in a desert of homophobia. I didn’t feel I’d convinced him of much. But when our banning became an issue, because of his history with anti-censorship struggles, he became an important ally. A few months later, he was reading a copy of Ilan Pappe’s The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine.

The battles over free speech also helped expose the fraudulent character of Brand Israel’s pinkwashing efforts. Israel uses the hard won advances made by its LGBT activists to promote itself as tolerant and gay positive, and hence to deflect criticism of its apartheid policies. But that message is hardly congruent with the Israel lobby’s alliance with homophobic city councilors in Toronto, or its bullying and attempts to destroy Pride by threatening its funding base. When the Jewish Defense League (JDL) issued a press release stating, “During the Nazi era, many high-ranking Nazis were gay,” as a prelude to its April 15th protest at the Pride Toronto offices, and when JDL demonstrators called counter protesters “fags,” they didn’t exactly portray themselves as paragons of tolerance or win friends in queer communities. Seeing the real face of the Israel lobby was an important learning experience for our allies.

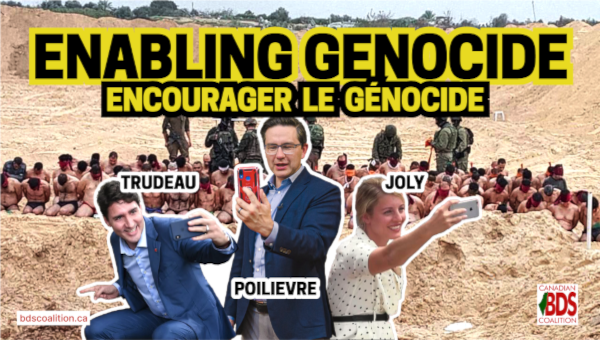

Finally, the free speech frame was an opportunity to talk about the attacks on Pride as part of a larger strategy by the Israel lobby to silence discussion – in universities and conferences, in the attacks on Kairos, Rights and Democracy, the Canadian Arab Federation, and in the government’s attempt to prevent pro-Palestinian British MP George Galloway from entering the country. These examples were eye openers for many of our free speech allies who began to understand how what was happening at Pride was part of a larger pattern of censorship, intimidation and silencing.

Freedom of Speech and Solidarity Work

In many ways the queer community is unique, and certainly the history of censorship that we have faced gives free speech arguments a special resonance. In other ways, however, our communities very much reflect values held by millions of people in Canada. Freedom of speech is one such hegemonic, democratic “liberal” value. It is therefore a terrain of struggle that we abandon at our peril.

First, our right to free speech is a basis of unity that is far broader and more accessible for those who are not yet comfortable with an analysis of Israeli apartheid. Building alliances around our right to speak is a major opportunity for us to establish relationships with other organizations and individuals and do our educational work outside our small circle of friends. It is an opportunity for us to bring Palestine solidarity from the periphery to the centre of popular discourse.

Secondly, the free speech frame jams Brand Israel messaging. It is very difficult to portray Israel as a liberal, tolerant, democratic state when its agents here expose themselves as censorious bullies, undermining such a basic liberal democratic value as free speech in Canada.

Finally, the need to defend free speech is of important practical consequence to our movement. So far, the legislative and municipal resolutions against the term Israeli Apartheid have been little more than symbolic. Yet, we are already experiencing a chill in our ability to rent locations for meetings and events. With a Harper majority, how far the repression may go is anybody’s guess. We can no longer take for granted our continued ability to speak and organize publicly. The silencing campaign is not a rhetorical issue; it is a real danger to our work. We need the broadest possible alliance to confront it.

For those who worry that participation in alliances around free speech and freedom of expression is a capitulation to liberalism, I urge consideration of the three demands of the BDS call: an end to the occupation and the removal of the apartheid wall, recognition of the equal rights of the Palestinian citizens in Israel, and the right of the Palestinian refugees to return to their lands and homes. These are all “liberal” demands. They are demands for basic human and democratic rights. They are neither revolutionary nor socialist. They do not propose any particular state formation. They merely call for compliance with international law. This is the basis of unity that Palestinian civil society has established for the international solidarity movement.

That basis of unity was crafted to enable the building of the broadest possible support in the context of liberal democratic countries. We should certainly work with anyone who supports these demands. And we should also be building bridges to all those who are prepared to defend those “liberal” democratic rights and freedoms that are the necessary context of our solidarity work. •