The Cartagena Accord: A Step Forward for Canada in Honduras

Honduras entered a new political phase on May 28 with the return of exiled former President Manuel Zelaya. His repatriation followed the signing of the Cartagena Accord between Zelaya, Honduran strongman Porfirio “Pepe” Lobo, and the governments of Colombia and Venezuela. From the vantage point of Canadian imperialism – a major external force in Honduras – the new topography of politics in the country is less a hindrance to, than an opportunity for, expansion on several fronts.

There is an argument, popularized by sections of the international Left, which presents Cartagena as a democratic breakthrough. That is, if judged against the repressive period inaugurated by the June 28, 2009 coup against Zelaya, post-Cartagena Honduras can be expected to adhere more closely to norms of human rights and to offer greater opportunity for democratic participation, relatively free of fear and intimidation. Such arguments conceal the systematic authoritarian continuity that underpins the new phase. The novelty of the period lies rather in the fresh packaging of the old dictatorship, something like a Bush war made palatable by Nobel Peace laureate Obama.

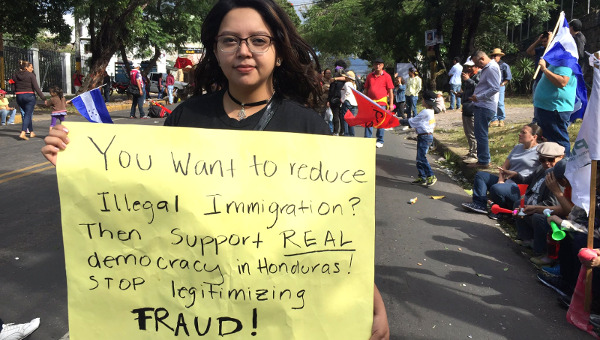

The construction of a democratic facade in post-coup Honduras found its earliest expression in the fraudulent November 2009 elections that ushered in Lobo and showed the door to Roberto Micheletti, the immediate successor to Zelaya following the coup. Cartagena then allowed the return of Zelaya to the country, the readmission of Honduras into the Organization of American States (OAS), and formal recognition by the Lobo regime of the new Frente Amplio (Broad Front) party of the official resistance. It is against this backdrop that the activities of Canadian capital in Honduras, and all their associated violence, are likely to intensify, with the support of the Harper government.

The Ottawa Connection

Honduras has become an important anchor to Canada’s engagement with Central America, an engagement driven by the promotion of strong property rights for capital and the containment of challenges to these rights through diplomatic, economic and security strategies.

Canada extended considerable energies in trying to ensure a particular ‘resolution’ to the coup. From the outset, the Harper administration sought to end the isolation of Honduras from the acceptable elements of the ‘international community’ – the country’s membership in the OAS was revoked because the coup violated this regional institution’s democratic charter – while at the same time securing its segregation from the orbit of Venezuelan influence and that of other Centre-Left governments in Latin America and the Caribbean. A brutally repressive, free-market regime, furbished with a hollow democratic shell, is the ideal model for the isthmus in the eyes of Canadian interests in Honduran mining, maquilas and tourism.

As a major source of foreign investment in Honduras, and with a strong predisposition toward neoliberal zealotry, Ottawa’s post-2009 coup policy has been to contain Zelaya and back pro-business Lobo. Zelaya was a member of a populist faction within the traditionalist Liberal Party whose modest social reforms and pragmatic shift toward closer relations with Venezuela’s Hugo Chávez did not serve to ingratiate him with the ruling coterie in the U.S. or Canada.

Opposition to Zelaya’s return from exile was at the core of the Canadian strategy in the months following the coup, as was the promotion of the San-José-Tegucigalpa Accord, which would have restored Zelaya as a mere figurehead president with only a month left in his term had it been ratified by the Honduran Congress.

The Harper administration recognized and supported the Lobo government despite the fact that it had come to office through elections that were boycotted by the popular resistance, offered no candidates who opposed the coup, took place in an atmosphere of high intimidation and military and paramilitary repression, lacked credible international observers and were deemed fraudulent by most Latin American governments.

Alongside Washington, Canada has been one of the lynchpins in a small clique of Lobo backers, working to normalize the regime’s international relations and lend it credibility by funding its Truth and Reconciliation Commission. From its inception, the commission was a farce, taking place as it did not in the aftermath of a violent conflict in which various actors were seeking peaceful resolution of differences in good faith, but while unidirectional military and paramilitary repression of unarmed civilians continued unabated. Serving a key role in the effort to present the Lobo government as one amenable to ‘reconciliation,’ the commission found in Canada an enthusiastic advocate – indeed, the Canadian state went so far as to provide a commission member, not coincidentally, a former diplomat now working with a major corporate law firm specializing in investment law and mining.

A large section of the Truth and Reconciliation report was just released on July 7, 2011, and thus we have not had the opportunity to study the tome in detail. Early analyses seem to indicate, nonetheless, that it is something of a concentrated version of existing ruling class apologia – that the violation of the constitutional order through a coup in June 2009 was one illegal step too far, but that Zelaya ultimately created the conditions for that coup through his own irresponsible behaviour. But we won’t find out what is in the rest of the report for some time: 10 per cent of this ‘truth’ report is being placed in a Canadian library and classified for 10 years.

In any case, it was not as though the Canadian government was waiting on the report to reach its final verdict. Earlier in the week, Canada Day celebrations in Tegucigalpa witnessed Lobo cavorting with the Canadian ambassador and a posse of placated Canadian investors.

The Bottom Line

Placing corporate profit above all other considerations, Canada has remained a steadfast ally of the Lobo regime. Facing incontrovertible evidence of systematic violations of human rights in Honduras, Canadian silence and complicity can only been seen in similarly lucid terms – as rationalized, centralized and strategic responses from the Harper government.

The Comité de Familiares de Detenidos Desaparecidos en Honduras (Committee of the Family Members of the Detained and Disappeared in Honduras, COFADEH), the most important human rights organization in Honduras, has documented that the scale of repression under Lobo has actually exceeded that under the Micheletti dictatorship that immediately followed the military coup. During Lobo’s first year in power (January 2010-January 2011) there were over 300 suspicious deaths of people associated with the Frente Nacional de la Resistencia Popular (National Front of Popular Resistance, FNRP, or the Frente), 34 targeted assassinations of activists within the Frente (with 3 more thus far in 2011), 34 killings of peasant activists involved in land struggles, 10 politically-motivated murders of journalists, and 31 slayings of members of the LGBT community, many of whom were associated with the anti-coup Resistance.

The laconism of the Canadian government in the face of this violent reality stems not from neglect or disinterest; rather, it derives from the fact that the violence is accompanied by, and in some ways acts as a necessary foundation for, the sociopathic commitment to foreign capital exhibited by the Honduran regime.

A recent conference held by the Lobo government for foreign investors, attended by a number of Canadians, was aptly named, Honduras is Open for Business. This is no false advertisement. Lobo appears to want to privatize everything under the sun. Rivers have been concessioned for dam building projects; the state electricity and telecommunications companies will likely be put up for auction; a new mining law is coming; large tracts of Garífuna (Afro-Indigenous) land on the north coast are being illegally sold for tourist development; and the constitution has been amended to allow for the creation of corporate-run city states (the so-called model cities).

Normalization of Authoritarian Capitalism

While the Canadian government, together with its U.S. ally, may have preferred tighter control over Honduras’s reintegration into the OAS, it nonetheless cannot be disappointed by the ultimate consequences of the Cartagena Accord. Promoted by Colombian president Juan Manuel Santos and his Venezuelan counterpart, Hugo Chávez, the Accord was signed on May 22, 2011 by Santos, a representative for Chávez, Lobo and Zelaya.

In return for Chávez’s backing of Honduras’s readmission into the OAS – achieved on June 1 – the Honduran government pledged to allow the safe return of Zelaya and former officials in his government from exile and to annul legal proceedings against the former president. Other commitments contained in the Accord already existed in ‘democratic’ Honduras, in theory at least: to act within the rule of law; ensure the protection of human rights; permit popular plebicites around political, economic and constitutional matters (one of the reasons for the coup d’etat was Zelaya’s effort to hold a referendum on the possibility of a constituent assembly); and to recognize any political party formation the FNRP should decide to build.

The Lobo government, in other words, committed to very little. There is no reason to believe, therefore, that simply because of Chávez’s support the Accord must represent a serious progressive step forward for the majority of Hondurans, or a setback for imperialism. Whatever Chávez’s motivation for promoting the Accord – strengthening diplomatic ties to Colombia to ensure the continuity of economic relations with a major trading partner, upstaging Brazil as the major diplomatic player on the South American left, or gaining political capital in the region by achieving a ‘resolution’ to the Honduran crisis where the imperialists could not – the Venezuelan government was not acting out of a genuine commitment to socialist internationalism, or international solidarity with the grassroots of liberation movements.

On what basis was it reasonable to assume that the human rights situation would change in any meaningful way under a new accord with the Lobo government given its record thus far? According to Bertha Oliva of COFADEH, immediately following the Accord two people were assassinated in downtown Tegucigalpa, mere blocks from the COFADEH office. Two weeks later, on June 5, three peasant activists in the Bajo Aguán region were assassinated near their San Esteban cooperative, while threats against other rank-and-file activists continued. On June 15, as if to send a clear public message that Honduras will not be bound by Cartagena, a judge ordered the house arrest of Zelaya’s former chief of staff, Enrique Flores, who had returned from exile on the same plane as Zelaya, on seemingly trumped up corruption charges.

By normalizing Honduran international relations through Cartagena, however, Chávez and Zelaya have bestowed a new legitimacy upon the Honduran government which will, if anything, consolidate Lobo’s neoliberal agenda. With its international pariah status extinguished, friendly governments and corporations can legitimate their old engagements and extend new ones with the Honduran regime under the auspices of Cartagena and the OAS.

The tired line to which Canada has been wedded since Lobo was elected, that the Honduran government is genuinely committed to national reconciliation and deserves reintegration into the international community, has received ex post facto sanction by Chávez and Zelaya. The basis for acceptable critique of the Canadian position has thus shrunk considerably, as was clearly indicated in the nonchalant absurdity of the intervention made by Canada’s representative to the OAS, Allan Culham, on June 1. Throughout the discussion around the readmission of Honduras into the regional body, Culham studiously avoided the descriptor ‘coup,’ referring instead to the long-awaited resolution to the “political crisis” of June 2009.

A Weaker Resistance is Good for Canadian Capital

The Cartagena Accord also shifts the terrain of struggle in Honduras. While there was certainly no absence of social movement organizing before June 2009, the removal of Zelaya from power, the repression that followed, and the economic policy of the coup forces gave rise to a new level of mass struggle and coordination of progressive organizations through the FNRP. The Resistance has drawn especially strong support in areas of the country under threat from mining, tourist, and biofuel developments, and has been able to mobilize at various points hundreds of thousands of people into the streets. The support the Resistance draws from the poor and working-class, compared to the more affluent nature of coup supporters, has by no means gone unnoticed by Canadian officials in Honduras, who have discussed it in their situation reports for Ottawa.

What seems clear from the process leading up to the signing of Cartagena, however, is that aside from some members of the leadership of the Resistance who are close to Zelaya, the membership of the FNRP was isolated from elite-level negotiations. It was Zelaya – still a member of the Liberal Party – rather than representatives of the various social movement forces in the Resistance, with whom Chávez communicated regarding the negotiations. Likewise, it was Zelaya and select members of the leadership who made the decision to sign the Accord with Lobo.

Zelaya was of course negotiating his return from exile, but the Accord’s implications, as noted above, extend well beyond his personal repatriation. The positioning of Zelaya as the singular figurehead of the opposition to the coup, by Chávez and Lobo alike, has provided him more traction in the Resistance. Zelaya, under the rubric of the Cartagena Accord, is now helping to steer the Resistance in a much safer electoral direction. Meanwhile, many of the key people behind the coup continue to wield political and economic power.

The Assault on Honduran Resources and Labour

These are positive developments for the Canadian state and capital. With the distraction of the ‘political crisis’ behind it, ‘reconciliation’ fait accompli, Lobo’s hyper-neoliberalism proceeding apace, and the Resistance contained, for the time being at least, prospects for Canadian expansion and intensification in Honduras have improved considerably.

Canadian companies have a stock of over $600-million in investment in Honduras, according to Ambassador Cameron Mackay, with particularly marked interests in the mining, maquila, and tourism sectors. Lobo continues to open the country up to foreign investment, and in the case of Canada, has entered into negotiations for the resolution of a free trade agreement. Canadian expansion, of course, comes at a cost for Hondurans. Mining and tourist projects involve displacement of communities and contamination of natural resources, while maquila companies like Gildan (one of the largest in the country) require a cheap, vulnerable labour supply.

Canadian mining companies have, according to Pedro Landa of the Centro Hondureño para la Promoción y Desarollo Comunitario (Honduran Centre for the Promotion of Community Development, CEHPRODEC), offered between 700 million and one billion U.S. dollars in new investment if a new law is passed. The toxic legacy of Canadian company Goldcorp is familiar to Hondurans, and thus the probability of even more companies invading local communities and ecologies is not being welcomed with open arms.

We had the opportunity to interview Carlos Amador, a leading environmental activist in the region of Valle de Siria. In a wide-ranging interview on June 17, he described the desecration of basic human and environmental rights committed by Canadian mining company Goldcorp and the various actions taken by the community to resist its activities. He described the role of Canadian mining corporations in the country as a new kind of “colonization.” A few days after our interview, Amador was arrested alongside another activist, Marlon Hernández, on trumped up charges relating to a protest action in early July. This arrest is merely the latest development in a long history of harassment and threats that Amador and other activists have had to endure. Amador’s release was secured in part through an international campaign of phone calls to the detention centre where he was being held. In the recent past, such campaigns have reportedly been crucial to stopping the torture of prisoners in detainment.

One of the largest Canadian projects under development in the country is owned by tourist magnate, Randy Jorgenson, associate of Pepe Lobo’s brother Ramón. The project, which will include a new $15-million (U.S.) cruise-ship dock, is being built through his company Life Visions near the north coast city of Trujillo on Garífuna land. A write up on the project in Canadian Business in June, 2011 refers, without irony, to its “bargain prices” as an attraction for retirees that “colonize the shorelines of Central American and Caribbean countries.”

During the Consejo de Ministerios (Council of Ministers) meeting in Trujillo in June, 2011, President Lobo feted Jorgenson with special recognition for his “contributions” to Trujillo, and topped it off with a commitment to build a road through the Garífuna communities to connect the tourist development to Trujillo. This meeting was followed on June 8 by another meeting between Lobo and Jorgenson in Trujillo. They were also joined by representatives of Canadian Shield Asset Management. The Canadians discussed a potential investment of $2-billion to build the first model city in Trujillo.

Garífuna activists we spoke to in late June argue that the project is advancing through the illegal purchase of titled land belonging collectively to their communities. Some of them have received death threats, which they suggest are a consequence of their vocal opposition to the development. We conducted an interview with Celso Alberto Guillén, a high-profile Garífuna activist, on June 22 in the small community of Guadalupe outside of Trujillo. Garífuna in Guadalupe have had ongoing conflicts with Jorgenson’s development project. Guillén explained that he lives in constant fear for his physical safety. He complained that he has been emotionally and psychologically traumatized by death threats launched against him by individuals he alleges are associated with Jorgenson. He has been personally threatened with a gun, and an individual approached his daughter recently and told her that he was going to put two bullets into her father.

If Canadian capital continues to expand in the tourism sector, the same is true in the maquila sweatshops. In February this year, after a series of meetings with Foreign Affairs and International Trade officials in Ottawa, the Canadian corporation, Gildan, announced a $100-million investment in a new sock factory. On June 19 we spoke to María Luisa Regalado, an activist and organizer in the Honduran maquila sector since 2006. Regalado lives in the industrial city of San Pedro Sula, and has worked extensively with the primarily female workforce of existing Gildan apparel factories in the country.

Regalado talked about a series of cases of women workers employed by Gildan who acquired various debilitating physical ailments due to the extremities of the job, and who were then summarily fired by the company. Once their utility to the bottom line had expended itself by way of the disablement of their bodies, the women were tossed into the streets like so many scraps of metal. The women found themselves without employment and without access to any social security. According to Regalado, “Gildan is one of the most exploitative companies operating in the country, and is one of the worst violators of human and labour rights.”

These stories, from the mining, tourist and maquila sectors, reveal the systematic character of the activities of Canadian capital in present-day authoritarian Honduras, rather than bad-apple anomalies that can easily be explained away. The Canadian government, in its enthusiastic backing of the Lobo regime, is the conscious diplomatic weight behind, and ideological defender of, these malign corporate practices. •

Thanks to Karen Spring for all her help organizing interviews.