Can Labour Precipitate a ‘Useful Crisis’ at Air Canada?

Shortly after being appointed Ontario’s Minister of Training and Education by Mike Harris in the mid 1990s, John Snobelen stated that it was necessary to create a ‘useful crisis’ in education to allow for neoliberal reforms. A number of ‘useful’ crises have been created in Canada over the last three decades by governments insistent upon radically restructuring public services. An earlier example was the privatization of Air Canada in 1988 by the Conservative government of Brian Mulroney in the midst of a period of global airline deregulation, started in the U.S. by the Carter Administration and expanded by Ronald Reagan throughout the 1980s.

Airline deregulation did reduce the price of air travel for consumers on some, but far from all, routes. The so-called ‘democratization’ of air travel was achieved, however, through rounds of failed start-ups, cutthroat price wars, declining service, incidental fees and downward pressure on wages and working conditions in the sector. For every WestJet and Porter (launched in 1996 and 2006 respectively, with particular forms of government subsidies in each case), there has been a Canada 3000 or Canadian Airlines. ‘New entrants’ adopt low cost models on select routes to challenge older ‘legacy airlines’ with large national and international networks, a higher paid workforce, and a range of commitments to provide services to particular communities. The result has been almost three decades of chaotic boom and bust cycles in the North American airline industry with few winners. Most recently, American Airlines (another so-called legacy airline) wants to use U.S. bankruptcy law to escape collective agreements and shed 13,000 jobs.

Reducing Labour Costs

Despite issues with over-capacity (Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario is now serviced from Toronto by 8 flights a day by two airlines), Air Canada is determined to reduce labour costs in its own operations and create genuine low-cost carriers (LCC) to compete with domestic (WestJet and Porter) and international (Ryanair) airlines. The strategy mimics Australia’s Qantas and its establishment of low-cost Jetstar. Air Canada’s success at establishing low cost branches has thus far been limited. In 2001, ACE Aviation Holdings (Air Canada’s parent corporation) consolidated its regional airlines and launched Air Canada Jazz the next year. Following major restructuring during bankruptcy in 2004, it sold off the lower-wage Jazz’s assets and today Chorus Aviation owns the company which was rebranded as Air Canada Express last year. Air Canada purchases seats from the company and manages its schedules and routes. Attempts to create ‘no-frills’ LCCs with Tango in eastern Canada in 2001 and Zip Airlines in the west in 2002, both failed. Zip lasted less than two years and Tango was folded into main Air Canada operations as economy class tickets.

Yet, Air Canada remains determined to achieve the flexibility needed from its 20,000 unionized workers to create new LCCs. The Canadian Union of Public Employees (CUPE) has considered allowing the development of a new LCC with lower wages and its own seniority list in exchange for the right to represent its flight attendants, but no agreement has been achieved through collective bargaining. The pilots have been more resistant and have staged ‘sickouts’ in March and again this week resulting in over 70 flight cancellations. These actions followed wildcat strikes on March 23 by machinists, baggage handlers and ground crew which cancelled 80 flights at Pearson International Airport in Toronto. The militancy has been a direct response to the heavy handed nature of the state as it systematically orders airline workers back-to-work, even before any work-stoppage occurs. Removing the right to strike limits the ability of airline workers to resist or negotiate the terms of any new LCC. More important, it allows the Conservatives to set further examples for public sector workers across Canada who may resist against austerity programs.

The unknown is whether or not airline workers can combine militancy and strategic capacity in the current competitive context to precipitate its own ‘useful’ crisis in the sector. Such a crisis could force an already interventionist federal government to consider alternatives to more destructive competition and lower wages and working conditions. Intuitively, it seems a stretch to expect any Conservative government to put itself in a position to have to re-regulate air travel, but is it outside the realm of possibility? Is the return of public ownership to the airline sector something that needs to be discussed seriously? Consider each of the following points.

Networks and Connectivity

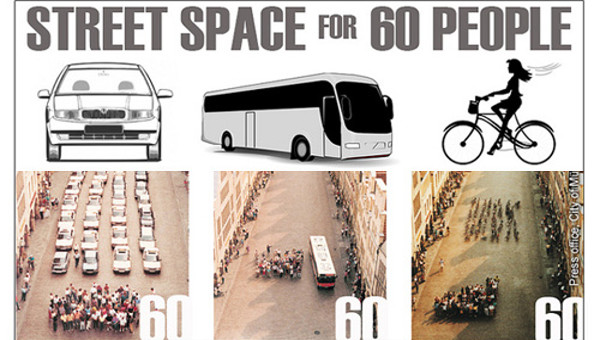

In advanced capitalism connectivity is a paramount concern in the linking of markets. Goods, services, capital and people must be able to circulate throughout the global economic system. National economies each strive to establish their own ‘hub’ airlines to facilitate the internationalization of capital and people. These large carriers guarantee cargo and passenger capacity, bring tourists to the markets, and support ‘hub’ airports which funnel air traffic to specific destinations and in the case of Canada provide a source of state revenue through airport fees. Airlines are also central to dynamic ‘innovation hubs’ coveted by global cities. The circulation of knowledge workers through Vancouver, Toronto and Montreal is limited if every international flight has to go through hubs such as Chicago, New York and Los Angeles.

In June 2011, the Harper government tabled back to work legislation forcing customer service representatives, represented by the Canadian Auto Workers (CAW), back to work in order to protect the ‘fragile recovery.’ The same excuse was used in October when the government ordered flight attendants back to work, leading to a disappointing arbitration decision for workers. During the recent March holiday break, the government once again tabled legislation removing the International Association of Machinists (IAM) members’ right to strike protecting middle class family vacations. Many on the Left and even some unions criticized the Harper government rhetoric of economic fragility as overstated. But, in fact, an airline strike would have significantly disrupted economic activity. Instead of downplaying this reality the Left should have recognized the leverage airline workers have strategically for the whole economy. Admittedly delaying or cancelling flights from Florida during March break does not foster wide public support. But delaying commuter flights between Toronto, Montreal and Ottawa for business professionals and bureaucrats would disrupt key networks without nearly as much complaint.

Global Airline Slump

Labour woes are far from the only challenge to Air Canada. The global airline is simply not a highly profitable sector as it is plagued with problems of intense competition and overcapacity. The large capital investments necessary and service costs require economies of scale and scope (achieved only with full planes) that are difficult to maintain in competitive markets. According to the International Air Transport Association (IATA), net post tax profit margins have never exceeded 5 per cent of total revenues in the sector since 1970. The recessions in the early 1990s, post 9/11, and following the 2008 global financial crisis resulted in losses of 5 per cent revenue. In 2008, the first year of the current crisis, the global industry lost $25-billion. At the same time, fuel prices continue to increase. While jet fuel prices have not yet reached their pre-recession peak, they have tripled over the last three years.

Yet global airline capacity continues to expand, especially in Asia. In 2012, it is estimated that the industry will add another 300 aircraft and in 2013 another 400. Airlines continue to compete rigorously, gambling that if they outlast competitors they will achieve future monopoly rents on routes they control. In order to increase international competition additional ‘open skies’ agreements are negotiated in which further winners and losers are determined, largely by the outcome of bilateral arrangements. In order to keep shareholders happy while tallying up losses, airlines have financialized their products like other industries. For example, Air Canada has spun of its profitable Aeroplan division managing frequent flyer points programmes and sold other profitable assets including Jazz.

Labour costs (outside of excessive CEO compensation packages) are simply not the central barrier to airline profitability. Massive fixed capital investments in a context of intensive capitalist competition in unstable markets are the problem. The fact that airlines are crucial to advanced capitalism and regional economies, yet the sector is highly unstable and unprofitable, is a contradiction facing national governments who wish to secure hub airlines for economic development.

The Limits of ‘Low Cost’ Carriers

Southwest Airlines was founded in Texas in 1971. The airline is touted as a successful model for global airlines; and it has been mimicked by both Porter and WestJet in Canada. Unlike the new entrants in Canada, Southwest is, however, highly unionized. It does manage to keep labour peace and claims to have a less hierarchical and a more ‘relational’ system of human resource management. Its savings also emerge from a simplified model of one class of service and the use of fewer airplane models which reduces service and training costs and increases productivity.

A second low-cost model is Ryanair, based in Ireland, founded in the 1980s and expanded in the 1990s with European airline deregulation. Hailed as part of the Irish miracle, Ryanair’s profitability has been based upon an aggressive union avoidance strategy through automated technology and the outsourcing of employees. The airline’s model is largely based on ‘no frills’ customer service and a series of surcharges to travellers. The airline lobbies for deregulation throughout Europe and will withdraw service from markets when it feels airport landing fees or taxes are too high.

The limit to this model is that the higher number of ‘new entrants’ adds further capacity while driving down standards. But there are other structural barriers limiting a successful LCC strategy for Air Canada. In Canada, the federal government charges large private airports significant fees. In other destinations airports are publicly owned and charge lower fees in order to attract activity and support new entrants in the early stages of their development. Given that low-cost carriers insist upon lower fees, the pressure to reduce rates also challenges governments. In Toronto, Porter Airlines was welcomed by the Toronto Port Authority as a means of reducing its deficit at its Toronto City Centre Airport (now called the Billy Bishop Toronto City Airport). Porter’s initial success was, in part, derived from its exclusivity rights to the convenient airport (ended in 2010) and the subsidies provided by the Toronto Port Authority (e.g., ferry services). How viable is Porter if the TPA withdraws subsidies and Air Canada Express competes with expanded services from the downtown airport?

The ‘Hollow Airline’ and the Regional Problem

Airlines such as Air Canada have clearly entertained ‘hollowing out’ their operations as a competitive strategy. An extreme model of the hollow airline would see all aircraft and airport slots ‘leased,’ service work replaced by technology (including pilots) or contracted out, and all ancillary services charged on a pay per use service (onboard food, toilets). The Canadian state is vulnerable as such restructuring of airline operations pays no attention to regional politics. Unions have tried to keep jobs where they are presently and have found local and regional allies, but appear to be limited in their ability to slow down the geographical realignment of Air Canada services.

On March 19, Aveos Fleet Performance declared bankruptcy. When Air Canada was privatized in 1988, the Air Canada Public Participation Act mandated that that airline had to service its planes in Montreal, Mississauga and Winnipeg. ACE Holdings spun off its Air Canada Technical Services (ACTS) maintenance unit in 2004 as it emerged from bankruptcy. In 2007, ACTS was renamed AVEOS and the company acquired further maintenance capacity in San Salvador to service the growing Latin American market. The company was profitable when it serviced Air Canada’s large aircraft, but Air Canada shifted its servicing of aircraft out of Montreal in recent months reducing revenues and inevitably killing 2600 jobs. The Quebec government has threatened to sue for violation of the 1988 agreement. Air Canada, founded as Trans Canada Airlines in 1936, has historically been headquartered in Montreal. There has been pressure, however, to shift operations, especially following the merger with western based Canadian Airlines in 2001. In January, Air Canada announced it would move 140 training jobs from Montreal to Toronto despite resistance from unions and local politicians.

Such political vulnerability leads to a number of questions for unions and workers in the airline sector. If Air Canada and the federal government are both vulnerable, why has organized labour been unable to leverage the sector to improve working conditions and extend unionization across the sector? Is it possible to use the sector as a strategic point of resistance to win gains for all workers? What vision and planning must airline workers undertake in order to build effective resistance?

Clearly there are some barriers to developing the power of labour in the sector. First and foremost is the fact that there is only one large highly unionized carrier in Canada. Even after deregulation, unions did have some ability to pattern bargain in the sector and play the airlines against one another when the major carriers were unionized.

The ‘heyday’ of union bargaining in the sector, however, should not be romanticized. Airline unions have never had complete control over the sector and structures were put in place to divide airline workers. In the U.S., airline bargaining was structured along the lines of the Railway Labor Act with unions divided by craft and class. Craft and class unions spread to Canada and today there are several unions representing workers at the same company (e.g, IAM, CAW, CUPE, ACPA – the Air Canada Pilot’s Association). These divisions challenge solidarity, but there are attempts by organizers to build links among the rank-and-file of different unions, something that has been limited in the past.

Another barrier to fostering worker solidarity and public ownership in the airlines is the fact that workers do not necessarily know what a state owned enterprise would mean for working conditions. Given public sector austerity, there is no guarantee that the tyranny of corporate ownership would be any better than the tyranny of public sector management. Until a clear model public sector industrial relations can be articulated, there is no incentive for workers to fight for public ownership and in the current context, break the law by not returning to work.

Some form of public ownership, however, ranging from a minority stakeholder position to full nationalization may be necessary to negotiate the big questions that will confront Air Canada and the Canadian state in the future. Even without public ownership, state involvement is required to guarantee the survival of a hub airline in the midst of persistent cycles of competition and instability. The federal government remains involved in the economic life of airlines despite so-called ‘deregulation.’ The state provides subsidies and guaranteed loans for new aircraft, protection against competition from international carriers (although sometimes poorly), and most recently, acts as a heavy handed arbitrator in labour/management disputes. Direct public ownership of one or more airlines would at the very least end the facade of a ‘private sector’ industry and create conditions for direct public accountability.

Some form of public ownership, however, ranging from a minority stakeholder position to full nationalization may be necessary to negotiate the big questions that will confront Air Canada and the Canadian state in the future. Even without public ownership, state involvement is required to guarantee the survival of a hub airline in the midst of persistent cycles of competition and instability. The federal government remains involved in the economic life of airlines despite so-called ‘deregulation.’ The state provides subsidies and guaranteed loans for new aircraft, protection against competition from international carriers (although sometimes poorly), and most recently, acts as a heavy handed arbitrator in labour/management disputes. Direct public ownership of one or more airlines would at the very least end the facade of a ‘private sector’ industry and create conditions for direct public accountability.

Public ownership may also be necessary to navigate the more difficult questions that may confront the industry in the future. In terms of green house gases (GHGs), air travel contributes about 5 per cent of global emissions. Air travel GHGs are, however, among the fastest growing source of emissions and the more radiative forcing gases (i.e., GHGs such as nitrous oxide which trap more heat in the atmosphere). If climate change is to be mitigated, air travel will have to be reduced. Domestically, this may involve a modal switch in North America to high speed rail (which would also generate significant construction and maintenance jobs). Internationally, any system of air travel rationing (although unlikely in the near future) would reduce air travel and employment. A publicly owned air line would increase the chances of a much more just transition for affected airline workers.

It is possible that the state could divest itself of all these problems and allow Air Canada to simply disappear or ‘merge’ with another international Star Alliance carrier (e.g., United, Lufthansa, Air France), but the political backlash from nationalists would be severe. There is also no guarantee that any carrier would want a large, debt-ridden airline. If Air Canada faces another crisis as it did in 2004, either from competitive markets, ecological disaster, political conflict, or perhaps even sustained labour disruption, public ownership may be the only option to preserve the airline.

At this juncture, the fight back against Air Canada alone is daunting. Any larger struggle for airline nationalization is difficult to imagine. Indeed, the Conservative government has used Air Canada as an opportunity to exercise power and demonstrate to all workers the extent to which the state can limit labour rights. For some, this is interpreted as another successful neoliberal intervention. There is, however, another view that back to work legislative action by the state indicates the growing weakness of neoliberalism. Neil Smith has argued that neoliberalism is ‘dead but dominant’ meaning that it is still a prevalent form of capitalism but it lacks political and theoretical innovation. Air Canada workers have not simply accepted employer arguments that there is no alternative but lower wages and greater work flexibility. Instead, they have forced the Canadian state to resort to one of the largest weapons in its arsenal in suspending the rights of association and collective bargaining to support a strategic sector. But airline workers will not be able to tackle reregulation and/or nationalization on their own as this will take social movement building and effective coalitions. Labour is, however, presented with an opportunity to perhaps precipitate and take advantage of a ‘useful crisis’ in a key economic sector rather than simply continue to accept private sector union decline and the degradation of work. •