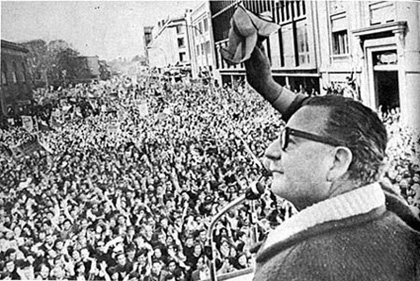

September 11, 2013 marks the 40th anniversary of the military coup in Chile, the 40th anniversary of the heroic death of Salvador Allende in La Moneda palace, and it will also mark the 40th year of the Chilean diaspora spread around the world. It is, undoubtedly, a relevant historical date for Chileans, Latin Americans, and for progressive people around the world.

This date has multiple meanings for the international revolutionary movement. Perhaps, the most important dimension for the historical memory of the people is the heroic combat of President Allende in the presidential palace for the dignity of the Chilean people, for democracy and socialism. After four decades of the coup, the figure of President Allende continues to grow and his example of decency, bravery and consistency defeat time and forgetfulness. His ideas attract the interest and guide the thinking and the actions of new generations of social and revolutionary activists in Latin America and other continents.

This date has multiple meanings for the international revolutionary movement. Perhaps, the most important dimension for the historical memory of the people is the heroic combat of President Allende in the presidential palace for the dignity of the Chilean people, for democracy and socialism. After four decades of the coup, the figure of President Allende continues to grow and his example of decency, bravery and consistency defeat time and forgetfulness. His ideas attract the interest and guide the thinking and the actions of new generations of social and revolutionary activists in Latin America and other continents.

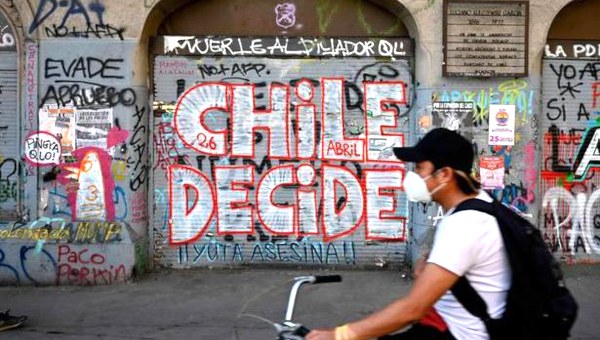

A different, but not less important connotation is that which points to the defeat of the Popular Unity government and its political project known as “via Allendista” (the Allendista way) or “la via chilena al socialism,” (the Chilean way to socialism), and the victory of the bourgeois and imperialist counterrevolution. It is not our intention to examine here the violent imposition of the Pinochet’s terrorist dictatorship, which allowed Chile to become the testing ground of the neoliberal policies that were applied later at a global scale. Rather we wish to propose that under certain conditions the “Allendista way” would have been successful.

Peaceful Road To Socialism

The tragic end of the Popular Unity government, for a long time, posed a fundamental question to the Latin American and international revolutionary movement: Was it or was it not viable to adopt the “peaceful road” toward socialism in pluralism, freedom and democracy proposed by Allende and his government in the 1970-73’s Chile?

The people and the Chilean working-class were still counting their casualties and mourning their dead, when some inside and outside of the left rushed to question and vehemently denied the viability of the Allendista project.

It was said that the institutional or peaceful way to build socialism was destined to fail from its very beginning. It was said that Allende’s way was pure illusion and that the classic Marxist theory had already indicated the impossibility of a successful implementation of such a way.

Today, forty years after President Allende’s death it is possible to sustain that “the Chilean way to socialism” as an untested revolutionary model to make profound social changes and build a more egalitarian and just society, was viable.

Some, the minority, had the lucidity to note that along with establishing the revolutionary character of the program and the alliance of social forces, what ultimately allows us to consider the process led by the Popular Unity government as revolutionary is precisely “the feasibility of it as a strategy of the proletariat that made possible the acquisition of the strength needed to build socialism in Chile,” (Socialist Party of Chile, 1974).

The most categorical response to that important question concerning the character of the Allende government does not come from the pompous institutes of the renovated leftist intellectuals but from the very core of the new revolutionary struggles of the people of Latin America to achieve profound transformations and to reposition socialism as an alternative and a solution to the current problems of neoliberalism and globalization being forced upon the mass of humanity.

The political process led by Allende is indeed a violently halted revolutionary project, but still despite its tragic consequences has been an unavoidable source of valuable lessons to successful revolutionary processes taking place in Venezuela and other countries of Latin America.

Lessons Learned from Previous Revolutions

Lenin, the great leader of the Russian revolution, reflecting upon the lessons from the Commune, the first proletarian insurrection said that:

“The sacrifices of the Commune, heavy as they were, are made up for by its significance for the general struggle of the proletariat: it stirred the socialist movement throughout Europe, it demonstrated the strength of civil war, it dispelled patriotic illusions, and destroyed the naïve belief in any efforts of the bourgeoisie for common national aims. The Commune taught the European proletariat to pose concretely the tasks of the socialist revolution.” (Lenin, 1982, p. 24)

And, in a particular reference to the struggle of the Russian working-class, Lenin, advised that it was important to learn from the lessons of the heroic Parisian workers. He said:

“… proletariat should not ignore peaceful methods of struggle – they serve its ordinary, day-to-day interests, they are necessary in periods of preparation for revolution – but it must never forget that in certain conditions the class struggle assumes the form of armed conflict and civil war.” (Lenin, 1982, p. 24)

As the October revolution was not possible without the Paris Commune the Bolivarian revolution in Venezuela would not have been possible without “the Chilean way to socialism.” Hugo Chavez the leader of the Bolivarian revolution in Venezuela noted on the occasion of the 39th anniversary of the coup d’état in Chile that it was important to learn from the heroic struggle of the Chilean people. Along with paying tribute to Allende, he warned that “a revolution may well be carried out through peaceful means, but cannot be unarmed. So unarmed was the socialist revolution in Chile that Allende, a medical doctor and an intellectual, ended up putting on a helmet and grabbing a submachine gun and becoming his own soldier,” (Chavez, 2012).

Allendista Way

Decades after the death of Allende, the Bolivarian revolution confirms that the strategy of the Chilean way to socialism was viable and the “Allendista way” under certain conditions was possible.

The originality of the Popular Unity and Allende’s political project consisted in transforming the class character of the bourgeois state without the condition of destroying it demanded by the general principles of Marxism. It proposed that by electorally controlling the most important component of political power, the government or executive power, it was possible, to control the other institutions (i.e., judiciary, legislative etc.) to gradually transform the character of the state. This task would be carried out without violence, without a civil war, and without a proletarian dictatorship.

The “Allendista way” developed over many years in the heat of social and political struggles of the popular movement of which Allende was always a visible participant. It was formulated in the ideological discussions that Allende himself brought forward when defending his strategic concept to build a new society. As a presidential candidate in four elections he had the unique opportunity to explain his vision to Chileans in every corner of the country.

From a theoretical viewpoint, when accepting the presidency Allende reiterated that:

“we are very clear as to who are the forces and agents of historical change. And, personally I know it very well that I can cite Engels to say that in the countries where the popular representation concentrates in it all the power the peaceful evolution from the old society to a new one can be conceived. What is desired can be done in agreement with the constitution once you have the majority of the nation behind you. And, that is the case in our Chile. Here, at last we have what Engels anticipated.” (Salvador Allende Foundation, 1992, p. 292)

The reality of the political struggle and the events taking place immediately after the electoral victory of September 4, 1970, clearly show that the intention of the local bourgeoisie and U.S. imperialism was to confront the popular movement in a different scenario from the democratic one chosen by the left leadership of Allende. This is demonstrated by the assassination of the Commander-in-Chief of the Army General Rene Schneider. Gen. Schneider, a constitutionalist general had stated that the army had to respect the Constitution and the Law and accept that Allende had become the President elect. He was assassinated by a Chilean right wing group of military officers and civilians, in October 1970. The logistics of this operation were supplied (guns and money included) by the Central Intelligence Agency through the U.S. embassy in Santiago. The purpose was to provoke a coup and prevent Allende’s election from being ratified by Congress, in November 1970. Later, as the Popular Unity government was implementing its program and the revolutionary process started to gain momentum another serious right wing military revolt took place on June 29, 1973. This military revolt known as “El Tancazo” made it clear that the Chilean bourgeoisie and the U.S. government had chosen violence to solve the political power struggle arising from the advancement of the popular movement challenge. Furthermore, according to the Church report, the Central Intelligence Agency of the United Stated (CIA) financed political parties, the right wing press and the terrorist group Patria y Libertad (Motherland and Liberty). Patria y Libertad blew up bridges, pipelines, electrical towers and carried out other terrorist attacks. Verdugo (2003) indicates that by 1973 there was a terrorist act every ten minutes in Chile.

With the perspective of time, we can assert that the tragic end of the Chilean Socialist project was not predetermined like a Greek tragedy. We can say that the chances of success or failure of the “Chilean way to socialism” were dynamic and in essence depended on the analysis and the political decisions made by the revolutionary leadership.

It is possible to argue, that the main cause of the defeat of the Popular Unity government in Chile is the inability of the Popular Unity’s revolutionary leadership, and not so much of President Allende, to develop a strategy that were to consider two aspects. On the one hand, the intelligent use of all the possibilities offered by the bourgeois institutions to consolidate and move forward the socialist agenda. And, on the other hand, it would consider as a real possibility the exhaustion of the bourgeois institutional path to continue the revolutionary transformations and prepare for the armed confrontation brought upon the popular movement by the U.S. and the local bourgeoisie, to resolve the issue of political power. Meanwhile the armed forces, persuaded by the U.S. and the local bourgeoisie, ceased to be neutral and ceased to guarantee the democratic process. The replacement of General Prats, a constitutionalist general who succeeded general Schneider as the Chief of the Army paved the way for the reactionary military officers to take control of the Armed Forces and stage the coup d’état on September 11, 1973.

Some analyses have rightly stated that “when a revolutionary process aborts a strategic possibility of victory, the main responsibility lies on the leadership of the working-class. In the Popular Unity experience the main failure resides in the fundamental task of building the leadership strength to lead the process to achieve power” (Socialist Party of Chile, 1974)

The Future of Revolutionary Struggles?

The inevitable lesson that the defeat of the Popular Unity imposes on the present and future revolutionary struggles is the need to design a strategy that contemplates the following two components: the tactical use of peaceful non-violent means; and, the anticipation and preparation for the armed confrontation to accede power. The recent revolutionary experiences in Latin America demonstrate that the neutrality of the Armed Forces is an important condition for revolutionary processes, to succeed. Like in Chile, in Venezuela the U.S. and its local allies have attempted military coups in order to reverse the Bolivarian process. Up until today the reactionary forces in Venezuela, Ecuador, and Bolivia have not been able to use the Armed Forces to help them to regain the executive power they lost through popular and democratic elections.

The Bolivarian revolution, learning from the Chilean experience, knew how to resolve this important strategic problem under the leadership of Hugo Chavez. He advised that, “to avoid armed wars the oligarchy and the U.S. imperialism have to be notified that this is a peaceful revolution, but it is an armed revolution, armed with ideas and guns to defend the people, its program and its hope,” (Chavez, 2012).

Forty years after his death, to remember Salvador Allende is neither a nostalgic act nor a gesture of loyalty to a person who interpreted the desire for revolutionary changes and social justice of an entire people. To remember Allende is, above all, to take responsibility for the past; to analyze the revolutionary experience of the Popular Unity and learn from it; to reflect on the political practice of Allende and to protect its legacy so that it can be applied to the new conditions facing the people of Latin America and the world.

Hugo Chavez understood this very well and shortly before his death, while paying tribute to Salvador Allende, said:

“Some theorized that the way to socialism was impossible through the electoral process and the peaceful, non-violent way. The years have passed and I think that what’s happening today in Latin America validates the attempt made by Allende and the Chilean people. It is not [intelligent] to say that it is not viable to create through peaceful methods the path to socialism.” (Chavez, 2012)

The Bolivarian revolution in Venezuela and the depth of the popular and democratic transformations taking place in Bolivia and Ecuador are reaffirming the viability of the Allendista’s way to build socialism.

In his first message to the Chilean parliament in 1970, Allende delineated with passion and conviction his utopian dream, (…) “am sure that we shall have the necessary energy and ability to carry on our effort and create the first socialist society built according to a democratic, pluralistic and libertarian model,” (Salvador Allende Foundation, 1992, p. 325).

On this September 11, in Latin America and around the world, thousands of tributes will be offered to Salvador Allende, the man who imagined the socialism of the 21st Century. •

This article is an expansion of an original work entitled “Allende’s Dream Was Possible” and published at the LARI’s website.