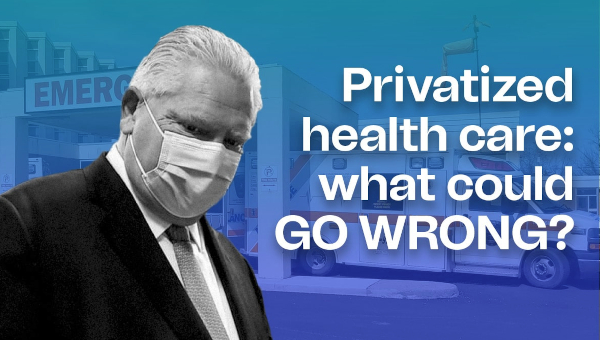

The welfare state has been under pressure since the mid-1980s and the onset of neoliberal economic policies across Europe. Capital has used the current crisis to intensify this pressure further. In Southern Europe, this is often directly enforced through the Troika (European Union, European Central Bank, and International Monetary Fund) in exchange for bailout packages, but in other countries such as the UK too, drastic cuts are justified by reference to increasing national debt and the global financial crisis. Trade unions and civil society organizations have struggled hard to defend the welfare state, but it has been a defensive struggle all the way and many aspects have already been lost. Trade union rights have been curbed in many countries, key industries such as telecommunications and postal services privatized and core services such as health and education increasingly marketized. Full employment policies have been a thing of the past for quite some time. In this blog post, I will reflect on the nature and contents of the welfare state and the possibilities of defending its achievements.

The welfare state is generally considered a major success of labour movements in industrialized countries. And indeed, as Asbjørn Wahl outlines in his book The Rise and Fall of the Welfare State [also see LeftStreamed No. 154], it was the strength of labour movements, built up in industrial struggles at the beginning of the 20th century, which forced concessions from capital against the background of regime competition during the Cold War. In exchange for continuing control over the means of production, capital accepted an expanded welfare state, policies of full employment and a strong role of trade unions in economic and social policy-making.

Class Compromise

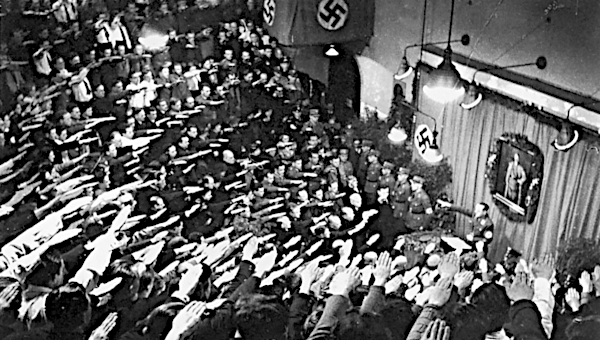

Importantly, however, this is only part of the story. As Wahl also makes clear, the welfare state included desirable qualities for capital too. Employers rely to a considerable extent on a healthy, well-educated and highly trained workforce in order to remain competitive. An efficient infrastructure and the provision of public services are also important to capital. In short, the welfare state has never been more than a compromise. In exchange for public services and employment, labour movements had to give up their ambition to reform or revolutionize the system beyond capitalism toward a socialist society based on the common, socialized ownership of the means of production.

If the welfare state is attacked now, then this implies that capital has renounced its side of the compromise. In times of high unemployment, there is a big enough reserve army of workers ready to snap up whatever job comes their way. Many labour intensive jobs are transferred to low wage countries, while capital increasingly focuses on the training of a small, highly educated workforce in industrialized countries. In any case, if there are not enough skilled workers, employers bring in migrant workers, who in turn are missing for development in their countries of origin. The general education of wider society is no longer a top priority.

“In this situation, defensive struggles to protect the welfare state are doomed to fail.”

The fact that capital was able to renounce its part of the compromise ultimately reflects the change in the power balance in society since the early 1970s. Against the background of transnational production and deregulated national financial markets, the balance of power has decisively tipped in favour of capital and at the expense of labour. In this situation, defensive struggles to protect the welfare state are doomed to fail. Worst excesses may be avoided, the dismantling of services may be delayed, but ultimately the welfare state will be gone.

What does this imply for the strategy of labour? In my view, the defence of something, which cannot be defended, is the wrong way forward. Is this not the time to return to the initial vision of transforming society beyond capitalism? A society in which universal access to health care, education, public transport, etc. is part of the very foundation rather than depending on the goodwill of employers? Is this not the time to mobilize the workforce afresh around a programme, which challenges capital much more fundamentally and puts forward the vision of a socialist alternative? •

This article first appeared at andreasbieler.blogspot.no.