A new departure for industrial policy in Europe is needed for five major reasons. The first is rooted in macroeconomics; exiting the current depression requires a substantial increase in demand, which could come from a Europe-wide public investment plan.

The second has to do with the changes in Europe’s economic structure resulting from the crisis; major losses are taking place in industries, a downsizing of the inflated financial sector is needed, and no new large economic activities that could offer new useful products and services and provide new employment are emerging.

Third, a new EU-wide industrial policy is needed in order to reverse the massive privatizations of past decades, which have failed to provide growth and employment.

The need for greater cohesion and reduced imbalances within the EU and individual countries is the fourth reason for a new EU-wide industrial policy. Current changes in Europe’s industrial structure open up a growing divide between a relatively strong ‘centre’ and a ‘periphery’ where a large share of industrial capacity is being lost.

Fifth, a new EU-wide industrial policy could become a major tool for addressing the urgent need for an ecological transformation of Europe. Turning Europe into a sustainable economy and society – reducing the use of non-renewable resources and energy, protecting ecological systems and landscapes, lowering CO2 and other emissions, reducing waste and generalizing recycling – goes well beyond the emergence of specific environmentally friendly new activities; it is a transformation that concerns the whole economy and society. In addressing all these priorities industrial policy can be an important and flexible tool. In order to implement it effectively, there is a need for new institutional arrangements and funding sources, new mechanisms of accountable governance, efficient and effective operation, systematic links between the EU and the national and local levels, as well as forms of democratic control with participatory practices.

Depression and Polarization in Europe

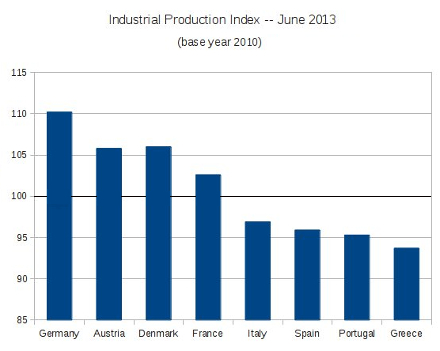

The crisis of 2008 has brought Europe to a depression. The continent has been divided between a ‘centre’ with financial and political power, and a ‘periphery’ with no political influence, high public debt, high unemployment and no hope for recovery. This polarization is evident in Eurostat data on industrial production. With 2010 data equal to 100, in June 2013 Germany’s index was 110.2, Austria’s 105.8, Denmark’s 106 and France’s 102.6. Conversely, Italy’s index was 96.9, Spain’s 95.9, Portugal’s 95.3 and Greece’s 93.7 (Eurostat 2013). Taking 2010 as the year of comparison, however, ignores the effects of the first years of the crisis. In Italy industrial production is now 25 per cent lower than in 2008, a fall that is common to most countries of the ‘periphery’ and is leading to a permanent loss of production capacity in most industries. As the ‘centre’ has largely preserved its industrial base and increased its exports to the ‘periphery,’ we are likely to face mounting trade imbalances within Europe that in the weaker countries might be addressed either by continuing austerity policies – depressing incomes and imports – or by renewed capital inflows further expanding private and public debt. In both cases, Europe’s periphery is heading toward a spiral of losses of income, jobs, production and exports.

In a context where European macroeconomic policies resist pressures to stimulate new demand and redistribute income, a generalized return to growth is unlikely. Without a substantial increase of public demand an end of the current depression is unlikely. Moreover, the aftermath of the crisis is likely to be marked by a more polarized industrial structure, where weak countries, regions, industries and firms become weaker, and where also the ‘centre’ may be left with lower demand, and a reduced ability to develop new technologies and economic activities. With a slowdown of overall growth in Europe and economic decline affecting several areas of its ‘periphery,’ change is likely to become more difficult. Europe as a whole would be stuck in its traditional economic trajectory – with sluggish markets, a heavy environmental burden, and growing inequality – while other advanced and emerging countries may move faster toward new knowledge, new products and processes and new sources of employment, supported by faster demand dynamics.

Five Reasons for a New Industrial Policy

There is no need, however, to accept such an outcome as inevitable. Europe is now facing multiple challenges: ending the depression; upgrading its economic structure with new job-creating activities; extending public action and public goods provision after decades of privatizations; reducing the polarization between ‘centre’ and ‘periphery’ resulting from the crisis; and moving toward a fundamental ecological transformation of the economy and society. An important, well known and effective tool could contribute to address all these challenges – a new Europe-wide industrial policy.

In Europe, industrial policy drove the highly successful expansion of production from the 1950s to the 1970s. In new industrialized countries it combines public and private efforts to develop knowledge, acquire technologies, invest in new activities, and expand foreign markets.

However, industrial policy fell out of fashion in Europe in the last two decades, when governments largely left decisions on the evolution of the economy to markets – that is, to large multinational firms – with waves of liberalizations and privatization of public enterprises. Policies lost their selectivity and were limited to automatic ‘horizontal’ mechanisms, such as across-the-board tax incentives for R&D and acquisition of new machinery, or incentives to producers and consumers of goods. The result has been a general loss of policy influence on the direction of industrial change and development in Europe.

Europe’s Missing Industrial Policy

European Union policies on the evolution of economic activities are now framed in the Europe 2020 strategy, approved in June 2010 by the European Council. It provides the new framework for economic policy in Europe, replacing the Lisbon Strategy that was supposed to inspire Europe’s policies in the previous decade. In the Lisbon Strategy the EU set the goal “to become the most competitive and dynamic knowledge-based economy in the world capable of sustainable economic growth with more and better jobs and greater social cohesion.” A comprehensive economic strategy was expected to be developed “preparing the transition to a knowledge-based economy and society by better policies for the information society and research and development (R&D), as well as by stepping up the process of structural reform for competitiveness and innovation and by completing the internal market; modernising the European social model, investing in people and combating social exclusion; sustaining a healthy economic outlook and favourable growth prospects by applying an appropriate macro-economic policy mix.” As pointed out by Lundvall and Lorenz (2011), after the mid-term evaluation of 2004-05 – and with right-wing governments replacing centre-left majorities in most European countries – the EU strategy was scaled down and focused on neoliberal policies for employment and economic growth.

The Europe 2020 strategy follows this same trajectory identifying three priorities: ‘smart growth,’ that is, an economy based on knowledge and innovation; ‘sustainable growth,’ that is, a resource efficient, greener and more competitive economy; and ‘inclusive growth,’ that is, a high-employment economy with social and territorial cohesion. By 2020 the EU is expected to reach five ‘headlines targets’ through a wide range of actions at the national and EU level, but the specific policy tools for achieving such goals appear limited. Eight ‘flagship’ initiatives are associated to priority issues for re-launching Europe (European Commission, 2010a).

The specific targets identified by Europe 2020 follow the footsteps of the Lisbon Agenda. The target of devoting 3 per cent of EU GDP to R&D expenditure is maintained. In 2008, R&D in EU-27 amounted to 2.1 per cent, with a highly uneven distribution across countries and no sign of convergence. Since then, the recession has led to falling expenditures and greater disparities. Innovation capacity is to be supported by the formation of human capital: The share of early school leavers should be under 10 per cent in 2020 (it was 14.4 per cent in 2009 in EU-27) and at least 40 per cent of the younger generation should have a tertiary degree (32.2 per cent in 2009 in EU-27). Again, progress toward such goals has been highly uneven and the recession has rolled back advances in ‘periphery’ countries.

The strategy includes a set of indicators from the 20/20/20 climate/energy targets established in 2009 by the European Council. The first one is the 20 per cent reduction of emissions by 2020 on the levels of 1990 (extended to 30 per cent ‘if the conditions are right’); in 2009, the EU level declined by 17 per cent, largely due to the economic crisis that has severely reduced output as well as emissions. The second target is the reduction of 20 per cent in the use of renewable sources (in 2008, it was 10.3 per cent). The third is a rise of 20 per cent in energy efficiency, with a move toward clean and efficient production systems with the potential to create millions of jobs.

The two ‘flagship’ initiatives devoted by Europe 2020 to innovation and industrial policy include the ‘Innovation Union’ (European Commission, 2010b) and ‘an integrated industrial policy for the globalization era’ (European Commission, 2010c). The aim is to provide the best conditions for business to innovate and grow, as well as to support the transformation of the manufacturing system toward a low-carbon economy.

As in the Lisbon agenda, industrial policy is based on a ‘horizontal’ approach, where the main policy tools are the provision of infrastructures, the reduction of transaction costs across the EU, a more appropriate regulatory framework favouring competition and access to finance. A significant role is ascribed to the ability of small and medium enterprises to promote growth and create employment. Key issues include the need to fight protectionism, increase the flows of goods, capital and people within and outside the EU, to exploit a more open single market for services and to benefit from globalization. This strategy confirms the rejection by EU policy – which began in the 1980s – of targeted industrial policies and state support for particular sectors, choosing a market based approach instead. Selective industrial policies continue to be considered ineffective by the EU, due to the difficulty of fine-tuning actions and evaluating results (Lerner, 2009).

Besides misplaced targets and a misleading approach, EU industrial policies have lacked adequate governance mechanisms, and no significant EU-wide resources have been made available to members states. Moreover, in this as in other fields of EU economic policy, the lack of democratic processes and broad participation in decision making has emerged as a major weakness of the present model of European integration.

When the crisis started in 2008 and austerity policies were imposed on Euro-area countries, the emphasis on fiscal consolidation and macroeconomic coordination sidelined any serious discussion on industrial policy. Europe 2020 is now in line with the neoliberal view that economic growth can be supported by the operation of markets and that fiscal consolidation and debt reduction create appropriate conditions for long term growth. Europe 2020 only suggests more resources for ‘growth-enhancing items’ such as education, R&D and innovation, at the expense of social expenditure, which is considered to be unsustainable (European Commission, 2010a, 2010c).

How Can We Change What is Produced?

A different policy perspective is needed, addressing at the European level the needs to end the depression and rebuild sustainable economic activities in a less polarized continent. Decisions on the future of the industrial structure in Europe have to be brought back into the public domain.

The general principles of industrial policy are simple enough. It should favour the evolution of knowledge, technologies and economic activities in directions that improve economic performances, social conditions and environmental sustainability. It should favour activities and industries characterized by learning processes – by individuals and in organizations – rapid technological change, scale and scope economies and a strong growth of demand and productivity. An obvious list would include activities centred on the environment and energy, knowledge and information and communication technologies (ICTs) as well as health and welfare.

Environment and energy: The current industrial model has to be deeply transformed in the direction of environmental sustainability. The technological paradigm of the future could be based on ‘green’ products, processes and social organizations that use much less energy, resources and land, have a much lighter effect on climate and eco-systems, move to renewable energy sources, organize transport systems beyond the dominance of cars with integrated mobility systems, rely on the repair and maintenance of existing goods and infrastructures and protect nature and the earth. Such a perspective raises enormous opportunities for research, innovation and new economic and social activities; a new set of coherent policies should address these complex, long-term challenges.

Knowledge and ICTs: Current change is dominated by the diffusion throughout the economy of the paradigm based on ICTs. Its potential for wider applications, higher productivity and lower prices, and new goods and social benefits should be supported. However, ICTs and web-based activities are reshaping the boundaries between the economic and social spheres, as the success of open source software, copyleft, Wikipedia and peer-to-peer clearly show. Policies should encourage the practice of innovation as a social, cooperative and open process, easing the rules on the access and sharing of knowledge, rather than enforcing and restricting the intellectual property rules designed for a previous technological era.

Health and welfare. Europe is an aging continent with the best health system in the world, rooted in its nature of being a public service outside the market. Advances in care systems, instrumentation, biotechnologies, genetics and drug research have to be supported and regulated considering their ethical and social consequences (as in the cases of GMOs, cloning, access to drugs in developing countries, etc…). Social innovation should spread in welfare services with a greater role for citizens, users and non-profit organizations, renewed public provision and new forms of self-organization of communities.

All these fields are characterized by labour intensive production processes and by a requirement of medium and high skills, with the potential to provide ‘good’ jobs.

Institutions, Governance and Funding of

Europe-wide Industrial Policy

Industrial policy has long relied on different mechanisms. On the supply side, public funds have supported selected R&D, innovation and investment efforts. Public investment banks and public enterprises – as well as non-profit foundations – have supported business start-ups in key fields with credits and venture capital and managed the restructuring of major production activities. Public, community and cooperative enterprises have a role in fields such as knowledge-based activities, environmental and local services where public goods and public procurement are prevalent.

On the demand side, far-sighted public procurement, the organization and regulation of markets with high growth potential, and support and incentives for early users of new technologies have helped ‘pull’ innovation and investments (Mazzucato, 2013). Similar tools have sometimes shifted production and consumption toward more sustainable patterns. In fewer cases, policies have ‘empowered the users,’ letting them define specific applications of existing technologies that may lead to new goods and services with large markets. Finally, policies have aimed at building closer relationships among all actors of national and European systems of innovation – firms, financial institutions, universities and policy makers – helping to coordinate decisions of public and private actors.

The funding for such policies has generally come from national public expenditures, the granting of public capital to state banks and enterprises and from financial markets through bonds with various degrees of public guarantee.

A proposal for a new Europe-wide industrial policy could be developed building on such previous experiences and on recent plans, such as the one proposed by the German trade union confederation DGB (2013). The following institutions, funding arrangements and governance mechanisms could be considered.

The Institutional Arrangements

The new industrial policy has to be firmly set within the European Union and – if required – within the institutions of the Eurozone. This is needed in order to coordinate industrial policy with macroeconomic, monetary, fiscal, trade, competition and other EU-wide policies, providing full legitimation to public action at the European level for influencing what is being produced (and how). Major changes are required in current EU regulations, in particular the ones that prevent public action from ‘distorting’ the operation of markets. The expansion of economic activities that markets are unable to develop should become an explicit objective of EU policy. The EU level is also crucial for funding such policy (see below). As this policy is likely to meet opposition by some EU countries, a ‘variable geometry’ EU policy could be envisaged, excluding the countries that do not wish to participate.

A close integration has to be developed between the European dimension – providing policy coherence, overall priorities and funding – the national dimension – where public agencies have to operate and an implementation strategy must be defined – and the local dimension – where specific public and private actors have to be involved in the complex tasks associated with the development of new economic activities.

Existing institutions could be renewed and integrated in such a new industrial policy, including – at the EU level – Structural Funds and the European Investment Bank (EIB). However, their mode of operation should be adapted to the different requirements of the role here proposed. While in the short term adapting existing institutions is the most effective way to proceed, in the longer term there is a need for a dedicated institution – either a European Public Investment Bank, or a European Industrial Agency – coherent with the mandate of reshaping economic activities in Europe.

A system could be envisaged in which EU governments and the European Parliament agree on the guidelines and funding of industrial policy, calling on the EU Commission to implement appropriate policy tools and spending mechanisms. In each country a specific institution – either an existing or a new one, either a National Public Investment Bank or a National Industrial Agency – could assume the role of coordinating the implementation of industrial policies at the national level, interacting with the existing national innovation system, policy actors, the financial sector, etc. More specific agencies, consortia or enterprises, with a flexible status but a strong public orientation, could be created (or adapted, if already in place) for action at the local and regional level and for initiatives in particular fields.

The Funding of Industrial Policy

Funds for a Europe-wide industrial policy should come from Europe-wide resources. As suggested by the DGB proposal ‘A Marshall Plan for Europe’ (DGB, 2013), funds could be raised on financial markets by a new European Public Agency; it could obtain the Europe-wide revenues of a once-for-all wealth tax and of the newly introduced Financial Transactions Tax; such income could help cover interest payments for the necessary projects that are not profitable in market terms. This arrangement would not burden domestic public finances and could visibly make the connection between policies for downsizing finance, taxing the rich, reducing inequality and the industrial policy that could lead to new economic activities and jobs.

An alternative may come from a more thoroughgoing European fiscal reform introducing an EU-wide tax on corporations, thus effectively eliminating fiscal competition between EU countries. Perhaps 15 per cent of proceedings could go to fund industrial policy, public investment, knowledge generation and diffusion at the EU level; the rest could be transferred to the countries’ treasuries.

For the group of Eurozone countries, financing through EMU mechanisms could be considered. Eurobonds could be created to fund industrial policy; a new European Public Investment Bank could borrow funds directly from the ECB; the ECB could directly provide funds for industrial policy.

Moreover, funding arrangements could be different according to the relevance of the ‘public’ dimension:

- The priority of public funds should go to public investment in non-market activities – such as public goods provision, infrastructures, knowledge, education and health;

- public funds and long term private investment should be combined in funding new ‘strategic’ market activities, such as the provision of public capital for new activities in emerging sectors;

- public support could stimulate financial markets with invest in private firms and non-profit organizations developing ‘good’ market activities that could more easily repay the investment.

In all cases, the rationale for financing industrial policy cannot be reduced to the financial logic of the ‘return on investment.’ The benefits in terms of environmental quality, social welfare, greater territorial cohesion and more diffused growth at the European level have to be considered, and the costs have to be shared accordingly.

The Governance System

The different options outlined above are associated to different governance arrangements of EU-wide industrial policy. As an example, we can assume that an EU public investment bank or agency – let us call it European public investment (EPI) – is created and similar organizations – national public investment (NPI) – act in each country. The European institution should be accountable to the European Parliament, which appoints its board in which representatives from business, research organizations, trade unions and environmental civil-society organizations should be included. No ‘revolving door’ between industrial policy institutions and private firms and banks would be allowed. The European institution should engage in consultation with EU political, economic and social actors for developing its proposed industrial policy, which should be approved by the European Parliament. Funds would then become available, and could be assigned to national institutions and specific targets and activities. Transparency in decisions would be required, and monitoring and evaluation procedures would be arranged.

The same governance system could be introduced in the national institutions in charge of coordinating implementation at the country level.

The fields that could be eligible for such industrial policy programmes can be identified within the broad areas outlined above. The countries and regions where such investments could be carried out have to be defined in advance, with the explicit aim of reducing the polarization that is weakening the industrial base of Europe’s ‘periphery.’ For instance, 75 per cent of funds could go to ‘periphery’ countries (Eastern and Southern Europe, plus Ireland); at least 50 per cent of them would be dedicated to the poorer regions of such countries; 25 per cent could go to the poorer regions of the countries of the ‘centre.’

Extensive public consultations and a democratic debate about what and how we produce could support these policy initiatives, building consensus and credibility for EU-wide industrial policy.

Opening up a debate on industrial policy in Europe is an urgent task. A wide range of ideas and proposals have to be shared and discussed. The political obstacles to such a new industrial policy are indeed huge, and major changes would be required in order to implement it. •

Paper delivered at the 19th Conference on Alternative Economic Policy in Europe, London 20-22 September 2013, and originally published on the transform-network website.