Demanding the Impossible: Struggles for the Future of Post-Secondary Education

There is growing acknowledgement emerging from student and faculty associations across Canada that there is a crisis in post-secondary education and a need for real change in the structure of university funding. This has manifested as a proliferation of student and worker unrest across the country and, indeed, the world; in 2008 and early 2009, there were dozens of university strikes and occupations across the world marked both by broader ideological challenges to the prevailing social order as well as increased repression from campus and state authorities. In Montreal, a protracted faculty strike was supported by an active student movement at UQAM and ended in an impressive victory. Meanwhile, student movements like “Opiskelijatoiminta” in Helsinki, and occupations of university space at NYU and the New School in New York have drawn inspiration from the sometimes violent demonstrations in universities across France and countless other actions in Italy, Greece, India and elsewhere.

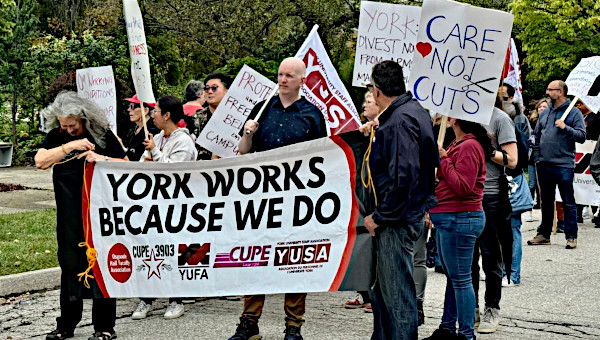

Nonetheless, it cannot be denied that there has been a simultaneous divergence of goals and strategies that has translated into fewer decisive victories in the long-term struggle for high-quality, accessible education.1 The recent strike of graduate students and part-time faculty at York University in Toronto over the winter of 2008-09 confronted these questions directly. Many competing narratives will emerge from the CUPE 3903 strike, given its untimely end at the hands of back-to-work legislation, but it seems clear that most of its participants agree on one thing: the state of post-secondary education is in a bad way and it is quickly reaching its breaking point. This breakdown, especially as it has played out at York, is well documented in Eric Newstadt’s “The Neoliberal University: Looking At The York Strike,” published during the first weeks of the strike. Given his thorough exposition of the extent to which York has embodied the troubling neoliberal shift, he can perhaps be forgiven for the pessimistic tone of his analysis.2

Building on Newstadt’s framework, this piece will sketch a brief history of the funding crisis in post-secondary education in the hopes of highlighting what I think are the crucial pressure-points in fighting back the trends toward inaccessible and watered-down educational experiences for students and low-reward, exploitative working conditions for teachers. Unlike Newstadt, I believe that there are significant openings for radical transformations emerging in the current moment, provided we build the necessary political groundwork to sustain larger, broader and more militant student and faculty coalitions that can challenge the neoliberal status quo. But, as Newstadt convincingly illustrates, this struggle requires a nuanced and critical understanding of how the neoliberal university replicates itself in ever more nefarious forms.

The problems facing post-secondary education today cannot be addressed by working within the constraints of current university budgets; mismanagement of resources is certainly a time-honoured tradition at places of higher learning, but it is not the source of the problem. Further, it is not sufficient to locate the source of our troubles at, for example, the provincial level and commit ourselves to lobbying campaigns at Queen’s Park. Such efforts have proven themselves unable to bring the leverage necessary to alter the austere climate of neoliberal legislatures.

In contexts where collective bargaining and normal progressive strategies no longer make inroads against the underlying distribution of power and resources, political advance seems to run up against unmovable obstacles and defeat sets in even when only advancing minor reforms or attempting to hold onto the status quo. Being politically ‘realistic’ either continues the spiral of decline or begins to confront the limits. Hence the slogan of the CUPE 3903 strike, taken over from the Situationists during the May 1968 social movements, “be realistic: demand the impossible.”

Chronic Underfunding and the Neoliberal University

The strike by CUPE (Canadian Union of Public Employees) 3903 set a record for university strikes in English-speaking Canada at 85 days. It is clear that the mobilization around the 2008 round of bargaining, and eventually the strike itself, was built around a growing recognition among academic professionals that the entire system of post-secondary education is eroding from the inside. Despite the fact that students are paying ever higher user fees in order to gain access to the intellectual establishment, their experiences once inside are increasingly mediated by an army of underpaid and overworked teaching assistants and contract professors who – far from being given the resources to adequately teach their students – are forced to take on hundreds of students each semester just to pay their bills from month to month. Graduate students, for their part, survive almost exclusively on student loans, amassing tens of thousands of dollars in debt on the promise of a sustainable tenured teaching career in their future. Only now are they beginning to discover that those careers are being eliminated in favour of contract work, and the skyrocketing attrition rates in graduate schools are a most immediate visible effect.3

Hardly cause for celebration, but you wouldn’t know it at York University. The institution was established in 1959: 50 years ago, as its media machine constantly reminds us with triumphant parties and ad campaigns.4 And, indeed, during the first two to three decades of its existence, York operated in a political context where government commitment to providing substantial funding for universities was rarely questioned – it was taken for granted in the golden age of Keynesian expansion that the best way for an economy to grow was for the market to operate under relatively tight control and for the state to use revenues from corporate taxes to support popular and important services like education, health care, employment insurance, community centers and other social programs.

With the crisis of corporate profitability in the mid-1970s, state policy in the advanced capitalist world came under hot contestation from the so-called neoliberals. Typified by characters like Ronald Reagan, Margaret Thatcher and Brian Mulroney, they preached an approach to politics that demanded tax cuts for the rich; de-regulation, freedom and flexibility for capital markets; and major cutbacks in government spending on social services. This shift took hold in earnest in the early 1980s and, not surprisingly, it meant that the funds that public institutions had come to rely on would no longer be available the way they were during the 60s and 70s. As governments strove to ‘balance their budgets’ in a context of significantly lower tax revenues – a product of the new climate where business was to be enticed by lower taxes and less regulation – public services were subjected to a new kind of operational logic.

Publicly owned enterprises like airlines and telephone companies were sold off to private bidders. Meanwhile, those institutions that could not be privatized without major public outcries, like hospitals and universities, were forced to survive in a climate that demanded austerity and profitability. With self-imposed limits on their resources, governments demanded that universities find ways of supporting themselves. Public institutions such as universities increasingly ‘marketized’ their internal administration and operational structures. This shift set the tone for the problems we are facing today and it is here that I would like to turn back to the current situation.

Increasingly since the late-80s, universities have operated along the basic principles of capitalist enterprise – keeping production costs down and maximizing surpluses – despite still being partially funded by the state. The result, predictably, has been a major shift in the lived experiences – educational and cultural – of those people most directly connected to the academic institution, ie., its teachers and the students. With decreased funding from the state, universities have come to rely more and more heavily on user fees – student tuition – for their basic operating budgets. At York, for instance, tuition fees accounted for over 37% of the university’s operating budget in the 2007/08 academic session.

As a result of the decrease in state funding, there has been consistent upward pressure on the fees themselves and a relentless effort to boost the numbers of undergraduate students pumped through the system. Classes that once held 50 students now hold 150; those that once held 150 now hold 500. In the meantime, federal and provincial policies engaged in a massive push to expand graduate programs in anticipation of the need to train new professors to accommodate for the growth in undergraduate enrollment. But, in a classic display of the idiocy of neoliberal governance, the same governments then turned around and started cutting the funds necessary to hire those new professors, so that more and more individuals are sinking tens of thousands of dollars into debt in order to complete graduate degrees with ever slimmer odds of ever breaking out of the cycle of precarious contract work that barely covers their basic needs.

In this context, it is no surprise that students increasingly view themselves not as participants in an intellectual pursuit, but as consumers who have paid for a service and expect adequate return on their investment; this mentality shaped the responses of many undergrads to the strike at York who felt that their ‘contract’ with the university had been breached. Universities simultaneously present themselves less as places of learning and more as places where job requirements are fulfilled; the universities’ job then is simply to find the most efficient way possible to help their customers complete the necessary steps for their later employment. Indeed, York’s administrators said it best themselves at a townhall discussion shortly after the strike was ended, when they claimed that students would not get a refund for lost class time because their tuition was “paying for credits” and the credits themselves would be delivered.

The CUPE 3903 Strike at York

With so many students passing through the university degree factory, the demand for teachers is increasing: after all, there is only so large that classes can get and someone, at some point, is going to have to mark all of those essays and exams. In a climate where funding is scarce, hiring full time professors to do all of this work just isn’t efficient – and thus we see the enormous expansion in the proportion of teaching done by teaching assistants (TA) and contract professors. These cheaper versions of professors do much the same teaching work and are often as qualified than individuals in the tenure stream to teach the courses they do. But as long as they are hired on a ‘part-time’ basis, they can be made to do the work for significantly less pay.

With the factory-model of education becoming increasingly institutionalized and accepted, successive administrations at York and elsewhere respond to chronic underfunding by raising tuition (and their own salaries) instead of demanding that the province provide the necessary support and it was this context that led to the CUPE 3903 strike in 2008-09. York University, like so many others, pumps as many ‘units’ through the degree machine as possible while making every effort to undermine the tenure system by replacing full-time professors with flexible ‘part-timers.’ And with the language of ‘hard economic times’ in tow, the new York University President Mamdouh Shoukri continued on with the relentlessly neoliberal administration of his predecessors, and avoided addressing the educational crisis they helped create (hoping to be rescued by the back-to-work legislation that eventually ended the strike).

The Union’s demands were centered around four key areas: 1) the creation of new 5-year teaching positions for long service contract faculty and the protection of rates of conversions from contract teaching into the tenure stream; 2) improvements to the overall funding packages offered to teaching and graduate assistants; 3) indexation of benefits to their 2005 levels to reflect growth in the Union’s membership; and 4) a two-year contract in order to join an effort by CUPE Ontario to coordinate bargaining for all locals in the sector. The demands around job security for contract faculty and conversions into tenure were at the heart of the strike and reflected a growing recognition that Canada’s third largest university is also one of its worst offenders when it comes to the casualization of teaching.

While there is much to be said about the specific tactical successes and failures of the CUPE 3903 strike, it is clear that the Union was united by its members’ commitment to the principles at stake in the strike. That is, while internal fissures were palpable and sometimes divisive (and often stoked by the troubled/troubling relationship between the local and CUPE’s national wing) there was little disagreement around the core issues. Even after two long, hard months on the picket lines, CUPE 3903 defeated a forced ratification vote by over 60%.5 Whatever the state of internal frictions, 3903 members remained stalwart in their insistence on working conditions that would improve the state of higher education.

Furthermore, it has become clear since the end of the strike that undergraduate support was likely much higher than was reported: witness the numbers of undergrads organizing and attending post-strike forums and the victory of a pro-strike student government despite vocal contestation from anti-strike students. The prospects, then, for collaborative work between students and teachers around questions of quality and accessibility of education are alive and well, making broader movements against the neoliberal university a distinct possibility.

Manage This, Mamdouh!

Which brings us to that perennial question: what is to be done? First, I think it is imperative to note that there are individual administrators and bureaucrats, like Presidents Shoukri and Marsden at York, who occupy their institutional roles in profoundly arrogant and self-serving ways. They have, and will always, manage the little funding that the university does have in whatever ways most immediately benefit themselves and their legacies.6 This should come as no surprise – the striking workers of CUPE 3903 regularly pointed to the injustice and hypocrisy of an individual making over $450,000 per year telling low-paid part-timers that they need to ‘tighten their belts.’7

Like any institution driven by the business model, there are always those who are well positioned to skim off the top and we should expect nothing less. Indeed, Eric Newstadt does well to draw out the way in which neoliberal administration consistently begets more administration; “an expansive administrative bulwark with a large and growing cadre of career bureaucrats and administrators” is cultivated and these administrators earn generous salary increases while students and part-time faculty have to struggle for every penny.8 But, while infuriating and unjust, that is not the fundamental problem, only a superficial element of it. Ultimately, even if senior administrators like Shoukri were to lower their salaries to match the average tenured professor, York University could not afford to eliminate tuition fees or properly support graduate students given current funding levels.

To this end, the goals are twofold – one significantly more important than the other. On the one hand, we need to get more funding allocated to the post-secondary sector. But this cannot be the exclusive focus: after all, there are other equally important sectors like health and social assistance that require adequate support too. In the absence of a revolutionary shift in the social order, we need to build broader projects for structural reforms that work to increase the overall extent to which public services are funded – ie. raising taxes on the most profitable businesses and wealthy individuals and using that money to support a wide range of social programs including education.

How should we go about doing that? It is here that I break from many of the student advocacy groups and large labour organizations. With absolutely no disrespect to the CFS (Canadian Federation of Students), the NDP, CUPE Ontario and others, which are filled with hard-working people engaged in important struggles, the project of lobbying governments to give more money to post-secondary education is woefully inadequate and bears little hope for carving out any real and lasting change to our situation. As the last decade has shown, perhaps most eloquently in the back-to-work legislation that ended this recent strike, no amount of lobbying focused almost exclusively at the parliamentary level is going to convince provincial leaders to spend more on education. Even the modest successes of the 2000s, including temporary tuition freezes in some provinces, have not produced long term results. Freezes have been lifted (as in Manitoba) and even where tuition itself was held in check, universities raised ancillary fees in order to make up the difference. Statistics Canada numbers consistently show that students’ overall fees are going up (with the notable exception of Quebec) while provincial funding for universities gradually sinks.9 The provinces themselves are caught up in a political climate that articulates for them a need to focus on the short-term goal of keeping spending down even if there are convincing arguments for the long-term benefits of funding education.

No, trying to influence the state with the strength of our logic and the picture of our poverty will not bear fruit. Instead, I believe we need to redouble our efforts to use our collective strength to force the universities themselves to address this crisis. If every worker at York University demanded a fair wage and refused to work unless they got it, and if every student demanded the elimination of tuition fees and refused to attend until that end was achieved, the administrators of the university would eventually have no alternative but to agree; the challenge now is to build up this understanding and motivate people to engage in this struggle. Elimination of tuition fees, for instance, is by no means unprecedented, despite the fact that it is viewed as an anathema in Canadian universities.10 If students and faculty could be convinced to take such relatively radical steps, their respective university administrators would be forced to ask for the same kinds of ‘bailouts’ that banks and financial institutions are getting; the provinces would have to choose between handing it over or seeing universities that support tens of thousands of students collapsing into bankruptcy.

As students and workers in the educational apparatus, we must be prepared to withdraw our participation entirely and let the pressure fall squarely on the university, because the province will not be motivated to fund post-secondary education when its willing technocrats like President Shoukri are finding other ways to balance the budget. Indeed, this is the central point here – Shoukri is a valuable asset not to the students and workers at York but to the state itself, because he and his staff are the ones who keep the pressure off Queen’s Park. Like a McDonalds “Manager of the Year” who is able to save money for the company by rescuing unopened ketchup packets from the floor and reusing them,11 Shoukri takes the scraps that the province sends to York and spins it into a functioning university by pumping students for tuition, by exploiting workers to the max and by soliciting support from the private sector.12

When all is said and done, York runs a budget surplus, and the province has all the evidence it needs to claim that their funding levels are fine and that increases are not needed; sure enough, when the Ontario budget came down after the strike was ended, it added nothing to post-secondary funding and actually encouraged tuition hikes of up to 36% over the next four years. And so, in his own way, Shoukri is indeed worth his $450,000 salary, because he is saving far more than that by ensuring that the government does not need to send York any more than the bare minimum in funding.

Realism and ‘The Impossible’

It is for this reason that I submit that the only way – short of a major Left turn in the prevailing social order – to address diminishing funding for universities is to ‘demand the impossible’ and leave university administrators no choice but to demand, in turn, adequate funding from the province. After all, that which is ‘possible’ for students and workers is determined by the extent to which a given university is supported by the state. Demanding more than what is currently ‘possible’ is simply insisting that the state alter the circumstances that define that ‘possibility’ until the people who use these institutions are satisfied by their experiences within them.

In order to force the hand of the province, we need to force the hand of the managers. Our responsibility is to make it impossible for Shoukri or anyone else to run a budget surplus at an underfunded institution by squeezing the very people it is meant to serve. We have to force York’s administration to pay its workers fairly and to reduce and eliminate the user fees it forces upon its students. It is incumbent on us as students and teachers to demand that which may be impossible in the current climate, leaving the universities no choice but to demand adequate support from the province. This is where our strength lies. All the lobbying in the world has not stemmed the tide of the neoliberal university.

Our only power is in the role we play in the actual functioning of these institutions – our labour as workers and our participation as students. Demanding the impossible is not some radical pipe dream designed by irresponsible troublemakers who want to be on strike forever. It represents a recognition that the only realistic means to improving the condition of post-secondary education is to give university administrators no choice but to demand adequate funding from the state or watch their institutions go bankrupt.

This represents the key pressure point where students and workers can have a real effect in forcing universities to operate in the way they are intended – that is, as institutions of real learning where anyone inclined can pursue the quest for knowledge and critical thinking. Neoliberal capitalism necessarily makes education a sideplot in the business of education, just as it makes caring for peoples’ health a sideplot in the business of health care. For those of us placed in these institutions – ostensibly public services that are partially privatized and subject to capitalist logic – it is our job to insist upon what may seem today to be impossible. That which will be possible tomorrow depends on what we do today and in a moment of capitalist crisis it behoves us to take full advantage of the radical possibilities opened up by the suddenly-visible failures that capitalism has created.

CUPE 3903 demanded a small slice of the impossible and, in the end, the only thing that could defeat the strike was back-to-work legislation. Next time, we must be more than one union – we must be a campus-wide movement. The province can legislate striking employees back to work, but they cannot legislate 50,000 striking students back to class. Student strikes in Quebec and, indeed, across the world, have shown that demanding the impossible can work13 – it’s time for the rest of us to get on board to ensure that the institutions and ideas we have committed our lives to, and that we believe so fervently in, are not destroyed by the vicious imperatives of a capitalist social order that would sacrifice its most valuable assets in the quest for immediate profits.

Naturally, this requires thinking beyond the usual trade union mentality where one single bargaining unit withholds its labour in the hope of accomplishing incremental improvements to its collective agreement. It requires a commitment to building linkages between student, graduate student and faculty associations that are prepared to push for radical solutions to problems that are sector-wide. The CUPE Ontario proposal for coordinated bargaining in 2010 is certainly a step in this direction, but it will require activists across the sector working together to build the political will to sustain struggles as long and bitter as the CUPE 3903 strike. Building that political consciousness will not be quick or easy but, as the Quebec example again illustrates, it is not unattainable. Furthermore, it is precisely by building that consciousness that these movements will be able to avail themselves of new, creative and perhaps more-effective tactics; where CUPE 3903 staged sit-ins and roving pickets, broader movements anchored in multiple universities could organize staggered full walkouts of classes and cross-campus information pickets, public campaigns and solidarity marches.

As for the workers in CUPE 3903, they may be down but they are not out. Eighty-five days on the picket lines did more to build political awareness than all the pamphlets in the world could have ever done. A new generation of activists in the storied local cut its political teeth in their confrontation with the neoliberal university and a repressive anti-labour state and media apparatus; there is no question that, as broader movements for radical change develop, the experience gained on the picket lines in 08-09 will be brought to bear and the lessons learned will inform the next round of struggle. •

I would like to thank Dr. Greg Albo in the Dept. of Political Science at York University for his very useful editorial insight.

Endnotes

- Of course, different definitions of ‘victory’ will produce different interpretations here. In the Canadian context, I would argue that the thrusts toward increased tuition, decreasing real wages for workers and overall corporatization of campuses indicates that big victories have been few and far between. Indeed, the resounding victory of CUPE 3903 in its strike in 2000-2001, as compared to the disappointing outcome of the strike in 2008-09 is but one example.

- Newstadt’s analysis of York’s neoliberal turn is as good as any that has been produced, but it is plagued by a consistently defeatist tone. In the first two paragraphs he indicates that the CUPE 3903 strike (then just over three weeks old) is only “mildly” aiding negotiations at other universities and that it may, rather, be undermining “the viability of similar strikes in the sector in the future.” Eric Newstadt, “The Neoliberal University: Looking at the York Strike,” The Bullet #165, December 5, 2008.

- According to information gathered by the Canadian Federation of Students (CFS) in 2005, graduate student attrition rates in Ontario rose to between 25% and 50% depending on the faculty and department. And informal studies indicate that these numbers have grown since then.

- Millions of dollars were raised in order to pay for the events surrounding York’s anniversary, which included black tie gala dinners and balls (the Red Rose Ball, at nearly $500 a plate, featured York’s 50th anniversary wine, grown at the Lailey Vineyard and specially bottled for the event), the purchase of every single advertising space at Yonge TTC Station for a month (so-called ‘station domination’ costs in the neighbourhood of $160,000), and a complimentary piece of birthday cake for a handful of lucky students in Vari Hall (let them eat cake?).

- All three units of the local defeated the ratification, with a total of 1466 ‘no’ votes which represented 63% of the total membership.

- It is well known, for instance, that President Shoukri is trying to build a medical school at York, despite the fact that existing programs are already overstretched.

- Ministry of Finance salary disclosure documents placed Shoukri at over $454,000 per year and showed that the position of York President had seen a 157% pay increase in the past decade. Former President Marsden continues to collect over $410,000 per year, presumably for participating in gala dinners, and countless other senior administrators broke $200,000. Bernie Lightman, an outspoken faculty critic of the CUPE 3903 strike earned over $150,000 per year. The average teaching assistant makes $17,000 per year which is reduced to $11,000 after tuition fees are deducted. For more on the so-called ‘sunshine list,’ see the Ontario Ministry of Finance website.

- Eric Newstadt, The Neoliberal University: Looking at the York Strike, The Bullet #165, December 5, 2008.

- See StatsCan figures.

- Germany, Ireland, Sweden and Finland are among the dozens of countries around the world that do not charge user fees for post-secondary education.

- These sorts of stories routinely appear in trade magazines and company bulletins. I remember working at a fast food restaurant in Winnipeg and being told by my manager that we should keep the napkins behind the counter and ‘only give them out if a customer asks.’ She insisted that the amount of money we were saving on napkins would make us the most competitive store in the province and earn us high accolades from the parent company. Unfortunately, when I quit the job, I stole every napkin on the premises, rendering the results of her managerial ingenuity unmeasurable.

- The gradual privatization of the universities is another aspect of the neoliberal university that this paper does not have space to address. Suffice it to say that one more way for managers to make up for shortfalls in funding is to turn to their corporate comrades, who are usually quite happy to invest money into R & D projects that will benefit their companies. The danger this poses to academic freedom is well documented – witness the case of Steph McLaughlin, faculty at University of Manitoba and Ian Mauro, a graduate student who, under McLaughlin’s supervision, created a research video on the effects of genetically modified crops on farmers in Western Canada. The video, which was critical of the infamous biotech company Monsanto, was suppressed by the university for over two years, just as Monsanto was relocating their corporate headquarters to the U of M campus, and was only released after a massive political organization around the censorship case. (Please see seedsofchangefilm.org for more details.)

- This short piece on the Quebec student strike of 2005 gives some background to what has been a consistently militant student movement since the 1960s.